China benefited from the wave of globalization in the 1990s and 2000s. Now that anti-globalization sentiments are growing in the US and EU, can Beijing help keep the world together?

Children wave flags to greet international leaders arriving at the West Lake State Guest House in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, September 4, 2016 / Photo by IC

When China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, the anti-globalization movement was already gaining momentum. Protesters gathered outside the meetings of the rule-making institutions that symbolized international economic integration: the WTO, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the G7 club of the richest developed nations. These institutions were also slated by academics, including Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, for imposing neoliberal doctrines on transitional economies. NGOs accused multinationals of destroying jobs and communities by pricing small firms out of the market.

But despite the opposition, the 1990s and 2000s witnessed a surge of globalization in major developed and developing economies. By joining the global value chain, China recorded record growth rates. It became the world’s largest exporter and second-largest importer in 2009, and it surpassed Japan to be the world’s second-largest economy the following year. In 2014, Chinese companies invested more in outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) than they received for the first time. That same year, a newly confident China laid out a range of roadmaps that could not only make China a world-leading investor and let it play a larger role in shaping global economic governance, but could also push globalization even further forward.

But today, opposition voices are strong enough to make a difference on globalization. Britain’s vote for exit from the European Union (EU) and the rise of ultra-nationalist US presidential candidate Donald Trump have set off alarm bells. Extreme nationalist parties in European countries, in particular France, Austria, and Denmark, are in power or close to it.

China hosted the G20 summit, described in an earlier 2009 Pittsburgh meeting as “the premier forum for … international economic cooperation,” in the city of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, in early September. Some agreements on facilitating global trade and investment were reached at the meeting, which analysts believe has sent the right message on countering the anti-globalization movement. But many are worried about whether words will be translated into action, and believe opening China up even more could help.

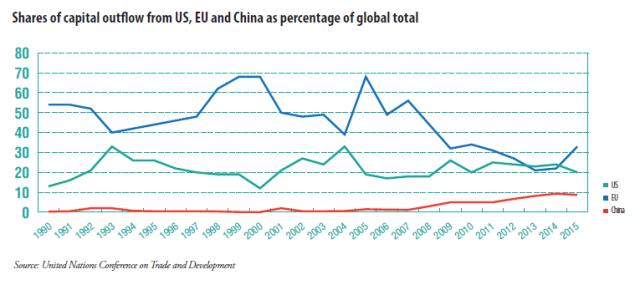

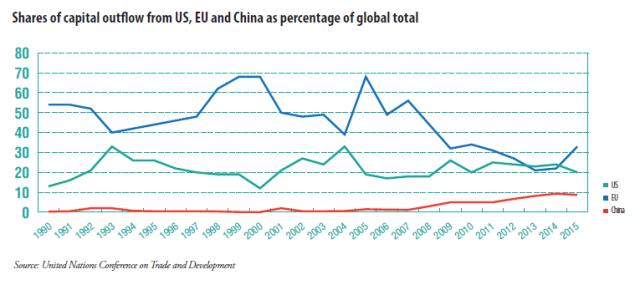

Global Bonds Globalization has been driven by capital, both from developed countries and regions like the US and the EU, and from and in China. Since 1990, developed economies have been the biggest provider and recipient of FDI, according to statistics from the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). The euro was launched in 2002 and the EU expanded to include more countries than ever in 2004. Meanwhile, financial deregulation in the 1990s in the US made it possible for Wall Street to invent and sell complex and ultimately unsupported financial derivatives to investors around the world, sowing the seeds of the sweeping crisis in 2007 and 2008.

China’s foreign trade doubled from 2.7 percent of the global total in 1993 to 5.9 percent in 2003, and increased by an average of 27.5 percent annually between 2002 and 2007, according to WTO and Chinese data. The EU has been China’s largest trading partner since 2004, and the US the second largest, and China has stayed on top of the league table of annual FDI inflow for developing economies since 1993. For years, foreign-funded enterprises contributed nearly half of China’s exports and a quarter of China’s industrial output, according to government data. Their operations helped develop and grow what is perhaps the world’s most versatile industrial value chain in China today.

This has produced a strong foundation for China to become a leading global investor, rather than just a manufacturer or trader. According to a recent UNCTAD report, in 2015 China was the third-largest investor among nations, following the US and Japan, for the third year in a row, and had become a “major investor in some developed countries.”

The Rhodium Group, a New York-based consultancy, said recently that capital inflow from China to the US in the first half of 2016 exceeded last year’s total, with more deals already announced. China’s record investments in the EU in 2015 are “in line with a broader shift of Chinese investment from developing and emerging to high-income economies,” according to Rhodium’s earlier report, published in partnership with Germany’s Mercator Institute for China Studies.

China is expected to invest more than US$1 trillion abroad in the next five years, as Chinese Premier Li Keqiang told his Central and Eastern European counterparts at a meeting in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, last November. In October, China’s currency, the yuan, will be included in the IMF’s special drawing rights currency basket, an official foreign exchange reserve held by IMF members. It is a milestone in the internationalization of the yuan, a process in which international financial hubs in the US and Europe are keen to participate. China has also devised or is engaged in an array of initiatives on free trade agreements, multilateral financial arrangements and cross-continental business connectivity, notably the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership in the Asia-Pacific, bilateral investment agreements with the US and the EU, the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank and the One Belt, One Road project.

These visions and developments, if they proceed as planned, will create a stronger economic presence for China and render its goal of a larger voice in international economic governance far more attainable.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Alibaba Group chairman Jack Ma display lobsters from Canada at the opening ceremony of Alibaba’s Tmall Global Canadian Pavilion, at Alibaba’s headquarters in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, September 3, 2016 / Photo by IC

Pointing Fingers The continued fallout from the global financial crisis has tested the bonds of globalization. The Trans-Pacific Partnership, one of US President Barack Obama’s most important initiatives to set global trade and investment rules on US terms, is at risk of being stymied by Congress or shelved by the next US president. Its European counterpart, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, is stalemated in negotiations.

China has been a big target of the wave of populist anti-globalization. European steel workers have taken to the streets to protest against imports from their Chinese competitors. Trump appeals to US white working-class voters who blame Chinese and Mexican workers for their job losses.

In July, the US and the EU declared that China would not receive market economy status automatically at the end of the year due to China’s overcapacity problems and limited market access for foreign investment. China has insisted it is the obligation of WTO members, as agreed in the protocols signed upon China’s accession to the WTO, to stop using other countries’ prices as a comparison point in anti-dumping investigations by December 11.

Joerg Wuttke, president of the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, has spoken of a “groundswell” of anti-China sentiment, not only among lower-income groups in Europe and the US who have long voted against pro-globalization politicians, but also among traditionally pro-China business communities that have benefited significantly from their China operations in the past 15 years. Despite recognizing Chinese investment’s contribution to the job market in their own countries, investors from those developed markets have found it difficult to buy the same assets in China that those Chinese investors are buying overseas, including power grids, banks, auto plants and robot makers, he said to NewsChina. New to its role as a big global player, China has “underestimated” both its influence on others and the shift of public opinion, he noted.

Fudan University Professor Feng Yujun said that Chinese enterprises should factor the retreat in globalization into their risk assessments when looking to do business overseas. At a July forum sponsored by the Phoenix International Think Tank in Beijing, he noted some new developments in globalization that could affect the expansion of Chinese outbound investment, including inward-looking tendencies due to the impact of new technologies and consideration of national interests in the US and Russia, US efforts to rewrite international trade and investment rules, and the ongoing rise in capital inflow into developed markets as a reversal of the trend in the early days of the financial crisis.

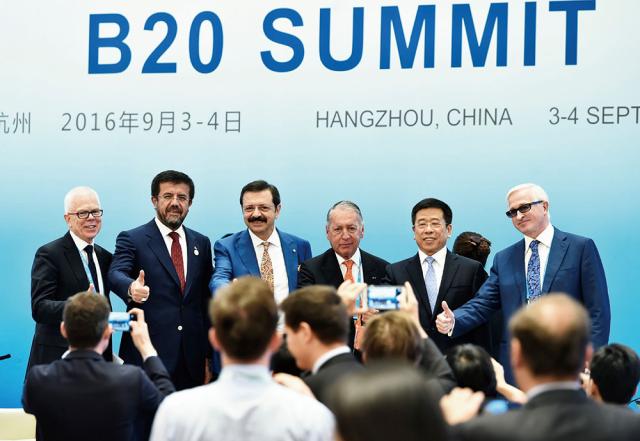

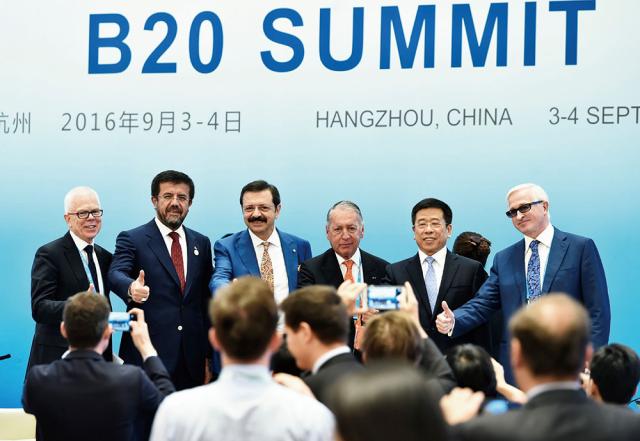

Business leaders meet in a session at the B20 summit, a gathering for the G20 business community, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, September 4, 2016 / Photo by IC

Openings It’s true that trade and investment didn’t get as much weight as financial and fiscal policies at previous G20 gatherings. But in Hangzhou, Chinese President Xi Jinping listed “setbacks to globalization” as one of the major challenges to global growth today. Boosting trade and investment worldwide was one of the four principal items on the G20 Hangzhou agenda.

Opening up trade and investment is one of the nine areas for structural reform identified in the G20 joint statement. Wang Shouwen, China’s vice minister of commerce, said at press conferences both before and after the G20 trade ministers’ meeting in July that trade and investment deserve a bigger role at the G20 if the group, the members of which account for 80 percent of global trade and capital outflow, really wants to address long-term issues of global growth. Wang described the guidelines on global investment reached at the meeting as a “milestone” and as the first step towards a comprehensive investment system. As he explained, previous efforts to create such a system mostly failed due to more than 3,300 fragmented investment agreements and conflicting interests between countries where capital originated and those to which it flowed.

G20 members have agreed to set up a global forum on overcapacity, with the support of the OECD. Reports on the progress on the forum are scheduled for the G20 ministers’ meetings in 2017. As a result of China’s proposal, G20 trade ministers have decided to meet regularly, and a working group on trade has already been established.

Yet analysts are divided on whether these nonbinding political commitments can be translated into action and thus offset the anti-globalization wave. Wuttke said the mounting “anti-establishment” sentiment in the outcry against globalization has made it very hard for European and US political leaders to adopt a more open attitude toward foreign investment and trade, and that this won’t change no matter who takes office. Shen Jianguang, chief economist of Mizuho Securities Asia Limited, shared this concern, saying in a September 9 article on the Financial Times’ Chinese site that the rising forces of anti-globalization have brought a lot of uncertainties to the implementation of the G20 declaration.

Others seem to be more optimistic. He Weiwen, vice president of the Beijing-based think tank Center for China and Globalization, does not think the next US administration will change its policies or laws encouraging foreign investment, nor be able to hold back the economic inevitability of globalization, despite presidential candidates’ remarks catering to anti-globalization sentiments. “The need for votes and the need for real business are very different,” he told NewsChina at a September forum sponsored by the International Think Tank of the Phoenix New Media in Beijing. However, he also said that Chinese enterprises should remember to take local needs seriously and pay particular attention to providing jobs and paying taxes. Taking these into account can help ease anti-globalization sentiments, he said.

Wuttke urged major economies to change themselves first by reducing their own protectionism, rather than pointing the finger at each other. He hopes that China, as the world’s biggest exporter and an increasingly important investor with its eyes fixed on becoming an economic rule maker, can take the lead in further opening up by continuing to ease import restrictions and putting more “dishes on the menu” of China’s assets that are open to foreign investment. After the initial opening of the manufacturing sector in the early years of WTO membership, further access by foreign business has also often faced nationalist resistance. The lack of market access to the Chinese service sector and some manufacturing sectors has become a political sticking point in China’s relations with the US and the EU in recent years.

It is in China’s own interests to further open up in order to aid its own growth, which could also help counter anti-globalization, according to He Weiwen. Chinese leaders have also reiterated the commitment to welcome FDI during the G20 summit. Indeed, the establishment of several free trade zones in coastal and inland provinces and cities shows China recognizes the important role of FDI in China, both in upgrading China’s economy or boosting domestic reform. FDI already helped play this role during the years of China’s economic take-off.

A more open China will be stronger, and more prepared to take the lead in countering the forces that risk tearing the world apart.

Old Version

Old Version