According to the 2024 State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture report by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global aquaculture production reached a record 130.9 million tons in 2022, surpassing wild capture fisheries (91 million tons) for the first time. China maintained its position as the world’s top producer, accounting for 36 percent of global output, followed by India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Peru. In 2023, China’s aquaculture area covered 7.6 million hectares, producing over 58 million tons of seafood, with per capita consumption at 50.48 kilograms – well above the global average.

Aquatic food consumption has been increasing for decades, particularly in China. From 1961 to 2021, global consumption per capita grew from 9.1 to 20.6 kilograms. Asia saw 1.9 percent annual growth over those 60 years, driven primarily by China, which went from 4.3 kilograms to 41.6 kilograms for 3.8 percent annual growth.

Traditional coastal aquaculture faces mounting challenges, including pollution, resource constraints and space limitations. Deep-sea aquaculture offers a promising alternative. According to Professor Wang Zhiyong of Jimei University’s Fisheries College in Fujian Province, deep-sea farming is an inevitable solution to the environmental degradation caused by high-density coastal aquaculture. In the Fujian city of Ningde – where 80 percent of China’s large yellow croaker is farmed – intensive farming has led to severe seawater pollution and significant economic losses.

“After more than two decades of high-density, mechanized overfarming, the coastal seawater environment is severely deteriorated. Prolonged overcultivation in the same areas, coupled with inadequate seawater purification, has led to frequent disease outbreaks, causing mortality rates of more than 50 percent among farmed yellow croaker and resulting in significant financial losses for local farmers,” Wang told NewsChina.

Given these challenges, expanding aquaculture into open-sea areas – particularly large yellow croaker farming – is seen as a necessary step forward.

In June 2023, eight government departments, including the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, issued China’s first official guideline on deep-sea aquaculture, limiting operations to at least 10 kilometers offshore and cages to waters at least 15 meters deep.

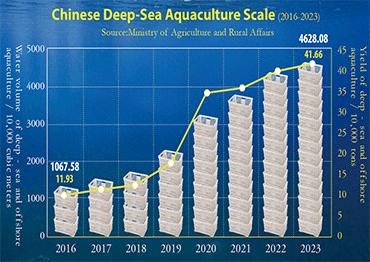

Between 2016 and 2023, China’s offshore aquaculture production grew from 119,300 to 416,600 tons, while the total aquaculture water volume expanded from 10.68 million to 46.28 million cubic meters. The sector has maintained annual growth rates of around 20 to 23 percent.

In 2020, Qingdao Guoxin Group, working with the Fishery Machinery and Instrument Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, launched Guoxin 1, the world’s first 100,000-ton aquaculture vessel. At 250 meters, Guoxin 1 was delivered and put into operation in May 2022. By September of that year, its first batch of framed large yellow croaker had reached the market.

Guoxin 1 features 15 aquaculture compartments and functions as a mobile farming and processing facility, managing the entire production cycle from stocking to slaughter. It operates across China’s deep-sea regions, including the Yellow, East China and South China seas, adjusting locations based on water temperature and environmental factors. For example, when farming large yellow croaker, the vessel moves between Qingdao and Fujian to align with the species’ natural migration patterns.

Local governments have introduced incentives to promote deep-sea aquaculture development. Provinces such as Hainan, Shandong, Zhejiang and Fujian provide subsidies ranging from 10 million yuan (US$1.37m) to 150 million yuan (US$20.6m) for aquaculture vessels and truss-type cages, whose rectangular structures are designed to withstand rough waters. Since 2018, China has deployed 40 deep-water truss-type cages, including Dehai 1, Penghu, Fubao 1 and the Jinghai series.

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, China has four aquaculture vessels, 40 truss-type cages and 20,000 “gravity cages,” which float on the surface as weights hang below to stretch out their nets.

Despite this progress, experts warn that domestic deep-sea aquaculture equipment remains in an early exploratory phase, with companies still developing sustainable business models.

The No. 1 central document of 2024, which laid out China’s rural and agricultural policy priorities for the year, reiterated government support for deep-sea and offshore aquaculture, continuing a policy focus introduced in 2023.

Following the successful operation of Guoxin 1, Shenzhen announced plans to build four 100,000-ton aquaculture vessels, while Zhuhai in Guangdong aims to construct eight to 10 such vessels within five years. In 2023, Guoxin Group also began building Guoxin 2-1 and Guoxin 2-2, upgrading to a 150,000- ton capacity. The company pledged to invest in 50 additional vessels over the next five years, forming 12 deep-sea aquaculture fleets for a combined tonnage of over 10 million.

According to an anonymous industry insider interviewed by NewsChina in January 2025, demand for deep-sea fish farming equipment in China is surging at an unprecedented pace. While the industry is expanding rapidly, challenges remain in scaling operations, ensuring sustainability and complying to global standards.

Old Version

Old Version