Efforts to track down ancient texts of the Naxiethnic group in libraries across the world are helping local priests revive a nearly lost ritual and inspiring the preservation of a fading ancient culture in the heart of Shangri-La

At daybreak, Mount Jiuxianfeng gleamed against the brightening azure sky above Rishuwan, a small village in Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Southwest China’s Yunnan Province.

Many know the region simply as Shangri-La.

Facing the mountain, Xi Shanghong welcomed his neighbors dressed in Naxi traditional costume to his courtyard home on November 6, 2023. Xi is the village’s chief Dongba, a priest in Naxi culture. Their arrival animated Xi’s courtyard, where an ancestral ritual not held in the village for around 70 years was preparing to begin.

Amid the chants and songs in local dialect, the smoke of burning twigs collected from pine trees spiraled up from an altar encircled by dried corn kernels glazed in cascading sunbeams. Xi had been preparing four years for the ceremony – with the help of researchers and ancient texts from half a world away.

In August 2019, Xi had obtained copies of two ancient Naxi texts from Zhang Xu, a veteran Naxiologist and president of the Beijing Association of Dongba Culture and Arts (ADCA).

The originals were acquired by Leiden University in the Netherlands, which houses 33 ancient Naxi texts acquired from a collector in the late 1990s. Over the past two decades, Zhang has been sending Xi photographed copies of such texts from collections across the world.

After reading the texts, which documented the routes and places his ancestors once migrated, Xi came up with the idea to revive the ancestor worship ritual, which traces the Naxi’s earliest origins and their later migrations.

Learning about these migrations is crucial to the ceremony, as they help to identify the locations of previous Naxi settlements.

“According to the Naxi religion, the souls of Naxi people who died of natural causes will be summoned to their ancestral places,” said He Shangli, a retired educator-turned-official with Sanba Administrative Village, whose jurisdiction covers Rishuwan Village.

These texts, housed in institutions such as the British Library, the University Library for Languages and Civilization Studies (BULAC) in Paris and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, have inspired Xi to recreate rituals that he believes will help to further reconnect Naxi culture with its distant past.

But with Xi firmly in his 80s, Dongba culture faces pressing challenges. Despite its distinctive religion, rites and written language, ancient Naxi culture is fading among younger generations, while the few who are enthusiastic about preserving the culture are divided on what to pass down, and how.

Xi Shanghong, the chief Dongba, or priest in Naxi culture, in Rishuwan Village, Shangri-La, Southwest China’s Yunnan Province, chants from a Dongba text copied from the Netherlands, November 2023. The copy enabled Xi to resume an ancestral ritual not held in the village for about 70 years (Photo by Bai Jinlai)

Ants and Elephants

According to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Program, which aims to document humanity’s collective heritage, Dongba served as a major conduit of Naxi culture for centuries.

In Naxi mythology, humans and nature are half-brothers born of the same father. According to the complete 45-volume set of Dongba ritual scriptures in Xi Shanghong’s possession, the deity of nature was traditionally enshrined in an annual ceremony at White Water Terraces (Baishuitai), a series of terraced spring waters with dissolved calcium carbonates at the foot of Haba Snow Mountain. At 5,369 meters tall, the mountain is sacred in Naxi culture and the highest in Shangri-La County.

“The ceremony, conducted for more than 1,000 years until the 1960s, demonstrated local people’s belief in their symbiotic relationship with nature, to which deforestation and overhunting are severe offenses subject to punishment from the gods,” He Shangli told NewsChina.

The ceremony ceased during the tumult of the Cultural Revolution (1966- 1976), but resumed in the early 1980s after China’s reform and opening-up.

“To preserve the spectacular beauty of the snow-capped mountains, lush woods, craggy gorges and deep canyons, our homage to nature corresponds with the country’s recent pledges to ecological conservation. In sharing these modern values, this ancient culture has reasons to endure,” He said.

According to He’s book Looking for the Ancient Migration Routes of Naxi People (2016), the Naxi began their migration about 4,000 years ago from the foothills of the Kailas Mountain Range in today’s Purang County, Ali Prefecture, Xizang Autonomous Region.

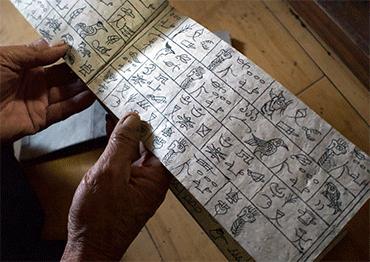

Over the centuries, Naxi branches migrated to the banks of the Wuliang River across western Sichuan and northern Yunnan provinces. They developed a written language to record stories about their culture, gods and ancestors.

With its complex forms and multiple meanings, Dongba script was used exclusively by priests. “In this unusual pictographic language, a single word could be a combination of several characters, and the meaning of each character varies according to context, like the character for ‘horse’ can mean ‘horseback riding,’ ‘horse leading’ or ‘an outing,’” He said.

Born to a long line of Dongba, Xi showed a natural talent for the language early on, learning from his father and through ancient scriptures. While sitting under the village’s inky night sky, Xi demonstrated his command of Dongba astrology, pointing out 28 constellations in the sea of myriad stars.

But experts have long debated its preservation, as some regarded certain aspects of Dongba culture as valueless superstition.

“With due respect to history, we should realize that when Dongba culture emerged, it was not very technologically advanced. People did not have the ability to explain natural phenomena,” said Lan Wei, a 90-year-old Naxi researcher of Dongba culture and author of The Amazing Dongba Characters of Naxi (2016), which is published in Dongba, Chinese and English.

“I don’t agree with many views or customs of the culture, like animals and humans sharing the same father and that women in ancient times should be buried alive to show their loyalty to their deceased husbands,” he said.

After being appointed curator of the Public Arts Gallery of Lijiang, Yunnan Province in 1977, Lan took an immense interest in Dongba characters.

“When I saw Dongba characters in the Lijiang County Library for the first time, I was deeply moved by their unique forms. I was also in awe of them... I felt like a kid standing in front of a master,” Lan wrote in the prologue of his 840-page encyclopedic book.

While the scholar is an atheist and views the gods and demons of Dongba religion through an anthropological lens, younger generations of his family connect with them on a more spiritual level.

His daughter Lan Biying, a research fellow at Lijiang Cultural Center, said she appreciates many of Dongba culture’s ancient tenets, such that the souls of every living thing are equal.

“I really agree with the belief that the soul of an ant equals that of an elephant,” she told NewsChina.

Naxi residents of Rishuwan Village, Shangri-La, Yunnan Province, chant in an ancestor worship ritual held in chief Dongba Xi Shanghong’s courtyard home on November 6, 2023 (Photo by Bai Jinlai)

‘Drop in the Ocean’

Nestled among mountains and gorges, the area known today as Shangri-La was first introduced to the wider Western world as the setting of the 1933 bestselling novel Lost Horizon by British author James Hilton, who never visited the region.

A blend of mysticism and Orientalism, the novel explores the relationships between humanity, nature and mortality from the perspectives of a group of Westerners at a fictional mountaintop lamasery. Coining the name “Shangri-La” to describe his hidden Tibetan utopia, Hinton’s tale captivated the imaginations of a generation.

Lost Horizon’s depictions of the region were partly inspired by photos of southwestern China taken by Austrian American botanist and anthropologist Joseph Rock, who submitted them to National Geographic magazine starting in 1928.

But in contrast to Hilton’s prominence, Rock lived a rather frugal existence in obscurity. The magazine eventually pulled support to continue his explorations of Dongba scriptures he found among Naxi’s indigenous community.

Unlike their Tibetan neighbors portrayed in Hilton’s novel, the Naxi originate from the Di and Qiang ethnic groups that for over 1,000 years were influenced both by Han and Tibetan communities.

Entranced by the unique culture and its writing, Rock sold all his assets in the US and moved to Kunming, capital of Yunnan Province in the 1930s to pursue his anthropological studies of the Naxi. However, Rock left in 1949 during the exodus of foreigners in the lead-up to the founding of the People’s Republic of China, taking with him a collection of about 8,000 Dongba texts. Most are currently preserved in overseas libraries, where many have been untouched for decades.

Following Rock’s departure, the Dongba familiar with the lost texts gradually passed away. Xi is among the few left with a command of the written language.

The culture perhaps would have faded even more had it not been for a documentary crew led by Zhang Xu that focused its lens on the village in the 1990s. Enamored with the culture and its customs since her first visit to Rishuwan Village, Zhang embarked on her overseas journey to collect copies of the missing texts for the remaining Dongba, helping them reconnect with the legends and stories from their childhoods.

“Every time I visited the libraries and museums, I would explain that the Dongba are getting older, and if they don’t see these texts in their lifetimes, we would lose this part of human heritage forever,” Zhang told NewsChina.

Over the past 25 years, Zhang has visited 12 libraries and museums in Europe, including the National Library of France, the British Library and Sweden’s National Museums of World Culture. She has also kept in contact with numerous scholars and librarians, some of which hope to further collaborate with ADCA in exploring their collections.

“Thanks to ADCA, BULAC received three new manuscripts for an exhibition organized in 2015 at BULAC in collaboration with Zhang. One is part of an epic poem recounting the struggle between two ancient Naxi clans: the Dong (which means “white”) and the Shu (meaning “black”). It is one of the three most important texts in Naxi literature,” Professor Soline Lau-Suche, deputy head of the collection development department at BULAC, told NewsChina in an email interview.

The library’s first collection of Dongba texts came from French explorer Prince Henri d’Orléans when he toured Dali, Yunnan Province in 1898. A decade later, pioneering French Orientalist Jacques Bacot bought back 18 manuscripts following his visits to Naxi villages. In 2009, Lau-Suche visited Lijiang to experience the historic and cultural value of the Dongba texts. During her trip, she was surprised to learn that her library was mentioned in an exhibition at the Dongba Culture Museum.

“That’s why when Zhang Xu contacted me three years later, I jumped at the chance, which represented a unique opportunity to learn more about these manuscripts, to make them known not only to the scientific community, but also to introduce the general public to Dongba and Naxi culture,” Lau-Suche said.

Apart from BULAC, ancestral worship was a latest program partnered between ADCA and Duncan Poupard, a translation professor specializing in Naxi literature at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

During Poupard’s first trip to Lijiang two decades ago, he found a dictionary of Dongba characters compiled by Chinese scholar Li Lincan (1913-1999) who spent half his career researching the ethinc cultures of Yunnan before serving as deputy curator of the Taipei Palace Museum.

“I arrived in the town and saw many Naxi writings. I bought a dictionary and it became like a hobby,” Poupard said.

Poupard paid his first visit to Rishuwan Village to study how Xi prepared to resume the ritual with Zhang’s coordination and grant Xi with funding from CUHK.

“Xi is an excellent ritualist with a wonderful memory of the cultural traditions he has inherited. He is one of the most knowledgeable Dongba alive,” the scholar told NewsChina after the trip.

Beyond research, Poupard also sought to help spread awareness of the culture.

“Academics have a very limited audience. I would like more people to learn about the Naxi language by coming to villages like this one, and able to use some Naxi, read some Naxi and talk with some Dongba, and find it a meaningful and interesting experience. It’s not easy,” Poupard told NewsChina.

Poupard’s visit was also part of Zhang’s documentary on the revival of Naxi’s ancestral worship. Unfortunately, Zhang was unable to join the team due to health issues.

“Our efforts are a drop in the ocean. But I still hope, for years or even centuries on, a few among the future generations take notice of our documentaries amid the plethora of videos and understand why we were so dedicated,” she said in an interview with NewsChina in October 2023.

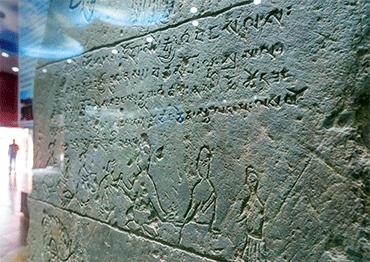

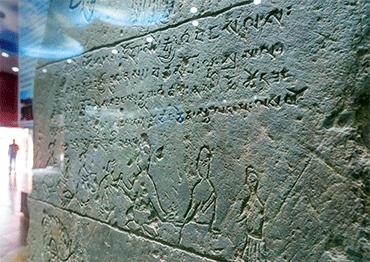

Pictured is an exhibition of artifacts and paintings concerning the rituals of the Naxi ethnic group at Lijiang Museum, April 6, 2023 (Photo by VCG)

A stone tablet from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and unearthed in Lijiang, Yunnan Province is displayed at Lijiang Museum, April 6, 2023. The tablet is a first-class national-protected cultural artifact (Photo by VCG)

Rustic Sensibility

Wearing a sleek bobbed hairdo, delicate makeup and a loose black-gray suit, Lan Wei’s granddaughter Xu Lanjing is full of urbane flair.

Born in 1985 to a well-off family in Lijiang, Xu was introduced to Dongba culture early on.

“I must have begun learning about it in my mother’s womb, as both my parents were working at the Dongba Culture Institute (DCI) in Lijiang,” Xu said.

After graduating from Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Xu worked as reporter and designer before making her fortune in e-commerce by selling Yunnan specialty goods. She now owns a small art studio where she paints and teaches children about Dongba art.

“Dongba and children’s paintings almost share the same simple and rustic look. That’s why I began teaching Dongba painting to children. I love the lines and colors of the paintings. They are more appealing to me than rituals and divination,” Xu said.

In one of her paintings, the Naxi god of wisdom holds two lotuses while sitting cross-legged. “To make my reproduction look more authentic, I used synthetic pigments to create a feeling of remoteness,” she said.

Xu also adds her own creativity into many of her works. For her 100 illustrations painted for the DCI, she used art apps on her iPad to give them a more modern look.

“Innovation should never be absent from the inheritance of traditional arts... Cultural heritage loses its vitality if it’s not integrated into daily life,” she said.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, the Naxi population numbered around 320,000 in 2021. Of them, some 200,000 lived in Lijiang.

Xu noted that while Naxi people take pride in their identity, Dongba rituals and characters are so disconnected from their everyday lives that they are viewed with reverence rather than exploration, let alone widespread acceptance.

“We speak Naxi dialect but few of us learn Dongba characters, not even our children at school,” a Naxi taxi driver in Lijiang told NewsChina.

However, more than 200 kilometers north of Lijiang, Rishuwan Village is ramping up efforts to pass down this legacy to younger generations.

Xi Dongqi, Xi’s eldest son, is expected to assume his role as Dongba and take the lead in preserving their ancient cultures, customs and religion. Only males can inherit the Dongba role.

“I cannot fall short of becoming a capable Dongba like my grandfather and father,” Xi Dongqi said at his home, where the three generations live under the same roof. Now in his 40s, Xi Dongqi has led rituals for over a decade and shares priesthood duties with his father, like worship and divination.

For him, divination poses the greatest challenge. It involves interpreting various signs to answer questions from believers about the future, such as observing the sunrise’s position or a mother’s age at conception to forecast the destiny of a newborn.

As for the future of Dongba rituals and Naxi culture, Xi Dongqi knows there is a long road ahead. but the texts and his father’s teachings can serve as a guide. “Throughout my practice, I’ve made some mistakes. But I still believe in and have affection for the religion, as it’s my duty to carry it on,” Xi Dongqi said.

Old Version

Old Version