Names are only labels; they do not define us. Our personalities are distinct and separate from them. As Shakespeare wrote so eloquently “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” However, research has increasingly shown that people hold stereotypes about other people due to their names. Moreover, there is even research to suggest that our names may influence our choices in life. This may be in part due to the way others around us treat us due to our names and the impressions they form of us due to them. In other words, if your name is perceived to be strong then people are more likely to interpret your actions as being strong and this may in turn boost your confidence, a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts. This might be good news for Superman, a Chinese boy I am familiar with, although I am not sure what it means for the little girl called MyFace.

As any international visitors to China will soon discover, it is quite normal for Chinese people to be given an unofficial English moniker. This practice is common even within families with little or no English knowledge. These names are obviously useful for Chinese people when interacting with foreigners, and they eliminate the risks associated with foreigners butchering Chinese names and naming customs in broken Chinese. Indeed, one of my friends has even adjusted her family name as well as her first name in English, which is a very unusual practice. She did so because her family name happens to be only a tonal mistake away from an expletive term that would make my grandmother faint.

English names have practical uses within certain social contexts for Chinese people. For example, in a surprising number of workplaces these English names are used at times between Chinese colleagues even when speaking Chinese. This is in part because they allow the avoidance of complicated hierarchical connotations associated with addressing people using formal Chinese names and titles. However, the choices that Chinese individuals make when selecting names for themselves or their children can sometimes leave foreigners bemused, amused and occasionally shocked.

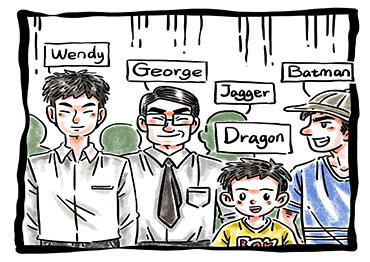

There are essentially four different categories of Chinese “English” names. The first is “adaptation” names, where someone bases their English name on their Chinese one. Done well, this can create a beautiful harmony. For example, someone whose Chinese name is Di Wen might select the English name Wendy. This creates a cross-cultural synergy that unifies the cultures of that person’s world.

The second category are “traditional” names. These are established names chosen from varied international sources. Names like George, William, Vivian and Grace abound, and probably form the single biggest category of English names. However, some choices can still raise an eyebrow or two. For example, Chinese people sometimes choose unorthodox spellings for traditional names, select rather antiquated names, select names from more obscure languages or countries, select trendy names that really belong in hippy communes in California, or ones that don’t traditionally align with their identified gender. Nevertheless, despite the occasional female Bob or Samuel, or the curiosity of Esmeralda, Zakiya or Crystal, at least these are identifiable as names.

The third category is what I like to refer to as the borderline names. These are names that hopefully make more sense in Chinese than they do in English. Many are related to animals or mythical creatures, others to natural phenomena. Examples such as Tiger, Rainbow and Dragon are popular and are rather fitting for small children. However, they seem less so when used by a middle-aged person within a business context. Other notable examples I have seen include Shark, Ducky, and I have even heard wind of a Dog.

The final category is what I call the eccentric. This category has no bounds, no limitations, and no end to surprises. Any international person who has lived in China long enough will know at least a few of these individuals because their names quite simply stick in the mind. Some are based upon fandom, such as Jagger, while others are based upon interests, such as Shopping. Others seem rooted in fantasy, such as Batman, while others don’t really bear thinking about, such as Hymen. In all situations one must question whether the individual, or their parents, were aware of the research linking people’s names with the way others treat them. Mind you, if Elon Musk has named his child “X Æ A-12,” then perhaps Skillet and Ultraman will be OK.

Old Version

Old Version