fter five years of preparation and construction, the highly anticipated Hong Kong Palace Museum (HKPM) opened its doors to visitors on July 3, with the opening exhibition showcasing 914 antiques from the Palace Museum in Beijing, also known as the Forbidden City, the imperial residence since 1421 during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) until the end of China’s last dynasty, the Qing (1644-1911).

Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District and the Palace Museum in Beijing signed a cooperation agreement to build the museum in June 2017.

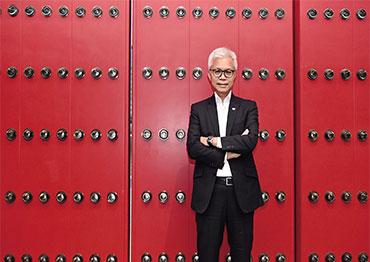

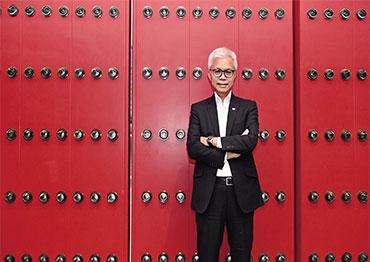

The opening came as the city celebrated the 25th anniversary of its return to China. In an exclusive interview with China News Service, Dr Louis Ng Chi-wa, director of the HKPM, revealed the stories behind Hong Kong’s newest cultural landmark.

Ng said the museum will help “build the city into a center for cultural and artistic exchanges between China and the world.” He stressed the HKPM is not a branch of the Palace Museum in Beijing, and is distinct from the Taipei Palace Museum.

Ng holds a PhD in history from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and a graduate diploma in Museum Studies from the University of Sydney. He has over 30 years of experience in museum management.

CNS: Historically, how has Hong Kong been linked to the Forbidden City? How has the Palace Museum in Beijing supported the HKPM? What are some of the local elements of the new museum?

Ng: Hong Kong has a deep connection with the Palace Museum. When some of the lost relics from the Forbidden City appeared in Hong Kong auctions in the 1950s, locals arranged the return of these national treasures. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Hong Kong collectors also acquired ancient Chinese relics and did not sell them.

Many of them wanted to preserve traditional Chinese culture and later donated their collections to the Palace Museum in Beijing. Parts of our opening exhibitions will present the stories of these collectors and donors. So, when Hong Kong was under British rule prior to 1997, many Hong Kong people willingly made contributions to serve their homeland. From this perspective, the establishment of the Hong Kong Palace Museum is partly because of historical development. We have brought some Hong Kong collectors’ donations from the Palace Museum back to the city for display.

We received a lot of support from the Palace Museum in Beijing. The two museums are not only strategic partners, but also brothers. The Palace Museum in Beijing supported us with a lot of human and physical resources, as well as a large amount of time as we jointly built the HKPM and work together to promote Chinese culture on the international stage. We have become part of each other. While preparing the exhibitions, people from the Palace Museum have been respectful to us and given us a lot of useful advice. They also gave us a lot of personnel support over the past year or two. Because different departments oversee the 914 artifacts on exhibition, they check every piece in storage to determine if it is fit for display in Hong Kong. Of course, our cooperation in opening the museum is just the beginning. We will have a lot of cooperation in the future, including exhibit rotations, academic exchanges and educational activities.

The HKPM is in West Kowloon, a prime area. It faces the sea, an important embodiment of Hong Kong. The Palace Museum in Beijing is characterized by its red walls, and ours by green waves. The architects did not design it as an enclosed venue, but one that complements the adjacent West Kowloon Art Park. Apart from connecting external spaces, the museum has three spatial and inter-connected atriums, an idea that the designers borrowed from the atriums in the Forbidden City. The ceiling in the middle atrium was built from aluminum. Resembling glazed tiles, this is a modern expression of traditional architectural elements. Visitors can see Hong Kong’s landscape in the atrium after they view the antiques of the Palace Museum in the exhibition hall, creating an intertwining experience [of modern and traditional landscapes]. So the overall design takes into consideration the relationship between Chinese culture, local elements and Hong Kong’s cityscape.

CNS: What do the historical value and cultural power of ancient Forbidden City relics bring to this modern cosmopolitan city?

Ng: I see their value in three ways: first, historical value. Many of them reflect the development of the country’s 5,000-year civilization. When people view cultural relics, they learn about history, including social and economic history. Second, artistic value. The beauty of art is permanent. That’s why paintings from the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties have been passed down for so many years. Third, emotional value. The country’s long-standing history will inspire the public’s awareness of China’s history and confidence in its culture.

When presenting antiques to visitors, we can’t just place them in a display case with a description like usual. We should instead tell and share the story behind each of them, such as how it was created and used. Some stories are interesting and involve anecdotes about family and love. That could easily make the visitors feel something for the antiques. We want to relate them to their modern lives. For example, when Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) emperors felt it was too hot, they had ice blocks [from lakes around the Forbidden City and in other royal parks] stored in the Forbidden City ice cellars [brought up to cool down]. Hong Kong is a place where East meets West.

Hong Kong’s researchers, curators and artists have their artistic techniques and expressions incorporated with both foreign and traditional Chinese elements. We have traditional exhibitions, as well as ground-breaking ones. For instance, we invited local designer Stanley Wong Ping-pui (also known as “Another mountain man”) to present the antiques of the Palace Museum. Wong is very good at expressing traditional culture with modern techniques. We also invited six young multimedia artists to create exhibits themed on the Palace Museum. Some use modern loudspeakers to present the music of the Forbidden City, while some others use landscapes, like mountains and rivers, to explain how clocks work. All these are connections that link tradition and modernity, showcasing the Forbidden City from a Hong Kong perspective. I hope all this will give visitors a unique experience from other palace museums in Beijing and Taipei.

CNS: What role will the HKPM play in cultural and museum exchanges between China and the West?

Ng: Connections with foreign museums is one of our priorities. Culture and art are non-political. Many foreign visitors love Chinese cultural and artistic exhibitions. We hope to promote our exhibitions overseas through our own network. Many in our team have work experience in the US and Europe, and are familiar with the tastes of Western audiences. Our exhibitions are bilingual in Chinese and English. Our overseas counterparts know that we are professional. This is what we are good at. Meanwhile, we can put on exhibitions from foreign museums and exchange events. We could also plan exhibitions focusing on China-West cultural exchanges and hold tours across the world. All in all, we hope to play the role of cultural coordinator.

CNS: How will the HKPM complement the adjacent M+ Museum?

Ng: I have calligraphy hanging in my office that says the Confucian motto “harmonious yet different.” The HKPM and the M+ Museum are both based in West Kowloon Cultural District, yet each has different focuses. While M+ looks at the world through its modern lens, it also sees China. And when we look at the world from the perspective of ancient China, we also see the modern world. We share some common goals and ideas, so we complement each other. Overall, when visitors see our traditional culture, as well as those from elsewhere, they would have an even deeper understanding of the world. China needs to understand more about the culture of the rest of the world, and that would give China a bigger say. For the rest of the world, deeper understanding of Chinese culture offers it a fair view of modern-day China. We hope West Kowloon Cultural District plays a more important role in promoting cultural and artistic exchanges between China and the rest of the world.

CNS: What would an ideal trip to the museum be like? What challenges might arise for the HKPM?

Ng: I don’t think you can fully experience the museum in one visit. One day might not even be enough for our opening exhibition. So, the experience should include several trips, because it may take more before visitors can truly appreciate the cultural and artistic journey. We would consider it a success if visitors can express what antiques impress them most. Of course, our biggest success would be to have them come back again and again, so going to our museum becomes part of their life.

There are two future challenges. One is good management, customer service and antique conservation, so visitors can really enjoy their experience in our museum. Second, excellent projects, talents and funding are needed to realize our vision and goals. To make ends meet, West Kowloon Cultural District Authority has to seek sustainable development. Besides admission fees, we will seek sponsorships. But we can’t go too far commercially, since it’s our responsibility to protect the Palace Museum’s brand. There are challenges, but we have confidence, as well as support from other organizations.

Old Version

Old Version