or many Westerners, bringing out a dusty bottle of fine aged Scotch is the way to let a guest know their visit is really a special occasion. In China, this is expressed by presenting a box of fine baijiu, or white liquor.

Fine baijiu (pronounced ‘Bye Joe!’) is served in special thimble-sized shot glasses. The alcohol content is so high that it can be absorbed through the lining of your mouth. Baijiu can commonly be found with a 60 percent alcohol level, and I’ve been served fine baijiu that was 72 percent – explosive enough for a Molotov cocktail.

Like many foreigners in China, my initiation to baijiu came during my student days, when my friends and I were so broke that we couldn’t afford US$2 beers. We would buy tiny pocket flasks of baijiu from the corner store for 50 cents. Gulping a small bottle down on a Beijing winter’s night had the force of drinking about eight beers in five minutes.

Students rarely get a chance to try good baijiu, but as the years went on, I had more chances, especially at office parties and weddings.

A lovely Chinese custom after a meal is for the guests to go around the table, offering a personalized toast to each person. These usually take the forms of expressions of gratitude or words of encouragement – or if you really can’t think of anything nice to say, a wish to get to know the person better.

Northeast China, where my in-laws live, is known for its rowdy humor. It’s the region of China where many top comedians come from. Northeasterners, like people from cold climates everywhere, also fancy themselves champion drinkers.

My Big Uncle Yu exemplifies this stereotype. He is friendly, funny, talks nonstop and loves to drink. He and his younger brother Old Yu are like a nonstop standup show.

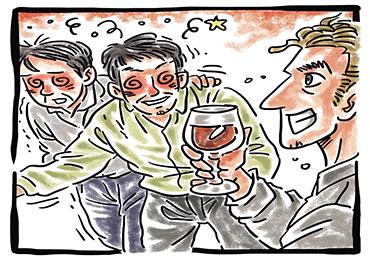

On the night of our first meeting, Big and Old Yu made the obligatory toasts to their 95-year-old father, who doesn’t drink as much as he used to, then set to work trying to drink me under the table. They were on their home turf, drinking their preferred drink, Kweichow Moutai, which goes for at least US$300 a bottle.

Big and Old Yu thought they had me beat when I ordered a round of beer, but were surprised that I just wanted something to wash the liquor down with.

In the end, Big Yu could not walk out of the room, and I heard his father scolded him the next day for getting so drunk.

In my experience, the key to successfully hanging out with Chinese men is following the secret contract – everyone tries to boost each other up, and make each other look good.

On a subsequent trip to Big Yu’s house, he showed me his basement karaoke room, which has a bar and a few cases of French and Chilean wine, and well as some Jack Daniels and of course lots of baijiu.

At his request, I picked a bottle of wine. He told everyone how knowledgeable I was. I responded by praising his extensive and tasteful wine cellar.

At dinner that evening, after we polished off the bottle I had chosen, which was quite tasty, he pulled out another bottle. He poured it into my glass, and I realized it had turned to vinegar – it was undrinkable. I switched to baijiu immediately, but to my surprise the other guests drank it without making a remark. To this day, I’m unsure whether they were just being polite, didn’t know wine turns to vinegar, or both. But I kept my end of the secret contract and didn’t mention a word.

One time, my sister and father came from Toronto to meet my in-laws. Big Yu sat my sister at the woman’s half of the table, where no one spoke English and the ladies nursed a single beer over the meal, if they drank anything at all, basically keeping quiet except to laugh at Big and Old Yu at appropriate moments.

I could see my sister was ticked off she was not invited to sit at the head of the table after coming all this way, so my father insisted she come join us. My sister proceeded to drink the Yus under the table, without appearing drunk in the least.

At the end of the meal, she asked, “OK everyone, where are we going next?” as Big and Little Yu’s wives helped them stagger out of their seats.

Our family achieved legendary status by heading out to a Western bar and not returning home until six hours later.

I still love drinking with my Chinese uncles, but I have noticed that since then no one tries to initiate a drinking contest. I guess I passed the rite of initiation into the family.

Old Version

Old Version