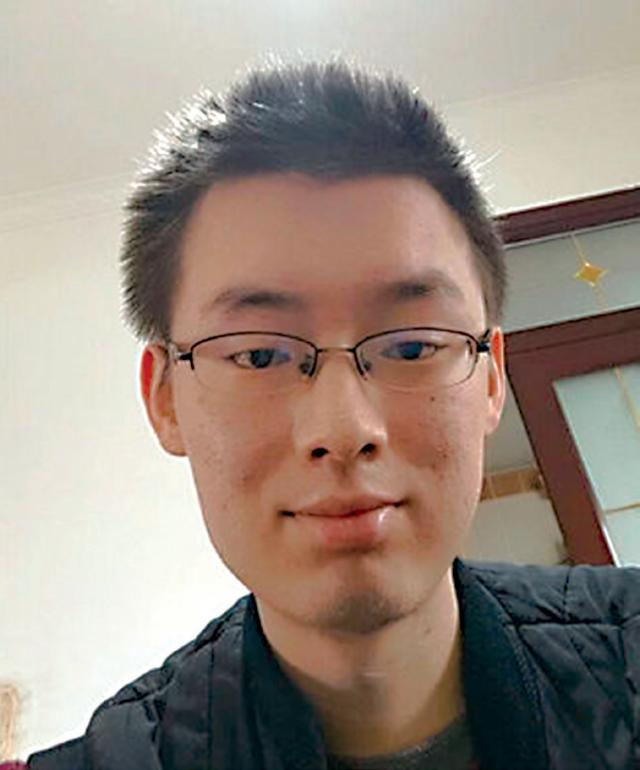

Wei Zexi, a 21-year-old university student, died from terminal synovial sarcoma, a rare form of cancer of the body’s soft tissue, on April 12, 2016.

Wei’s parents said they spent more than 200,000 yuan (US$31,000) on a form of immunotherapy called DC-CIK at the Second Hospital of the Beijing Armed Police Corps.

This expensive barrage of procedures, according to the hospital, uses healthy cells generated by a patient’s own immune system to kill cancer cells.

Wei, a computer science major at Xidian University in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, received his cancer diagnosis in 2014. He underwent surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy in other hospitals before turning last year to the immunotherapy offered at the Beijing hospital.

From September 2014 to the end of 2015, Wei received a total of four courses of treatment at the military hospital, his program outsourced to a private healthcare provider.

The hospital told Wei’s parents that their son would be able to survive for at least another 20 years due to the highly effective treatment.

He was dead within 18 months.

Chen Xiaobing, a professor at Zhengzhou University and deputy director of internal medicine at the university’s affiliated Henan Cancer Hospital, told NewsChina that hospitals and doctors had limited knowledge and experience about the specific form of cancer that would claim Wei’s life.

Synovial sarcoma accounts for just 9 percent of all detected soft tissue sarcoma cases in China, which, in turn, constitute a mere 1 percent of all diagnosed malignant tumors in the country, according to the Chinese Expert Consensus on Diagnosis and Treatment of Soft Tissue Sarcomas, which was compiled last September by the Society of Sarcoma under the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association.

“How could [the hospital] make such a promise?” Chen asked.

Zhang Lei, a council member of the Chinese Society of Biotechnology (CSB) and senior engineer at Tianjin Hualida Bioengineering Co., said Wei’s death was just the tip of the iceberg.

“Immunotherapy is being touted as a panacea for almost all diseases,” Zhang told NewsChina. “Practitioners in this field had deployed ‘land mines’ long before this incident.

Wei was just the detonator.” Over the years, Chinese investors have been closely following worldwide developments in biomedical technology. By taking advantage of regulatory loopholes, these moneymen have lost no time in promoting often partially complete research findings lifted from overseas medical tests and repackaging half-baked treatments as cutting-edge cure-alls to sell to desperate patients like Wei.

Placebo Shortly before his death, Wei posted a video online saying he had chosen the Second Hospital of the Beijing Armed Police Corps because of its high ranking in the search results of China’s leading search engine, Baidu.

It remains unknown whether Wei’s death was caused or accelerated by the treatment he received, or if the treatment was a simple placebo, but authorities later confirmed the therapy employed to treat Wei was still in the research phase and not approved for clinical use. A separate investigation also confirmed the hospital’s questionable business model, which involved outsourcing to private medical companies, as well as Baidu’s “misleading” placement of medical ads as factors in Wei’s case.

Regulators responded to mounting public condemnation by demanding an overhaul of healthcare ads carried by Baidu. The Cyberspace Administration of China said Baidu relied “excessively” on profits from paid listings, the practice of ranking search results according to the prices advertisers pay, which “compromised the objectivity and impartiality of search results” by not clearly labeling such listings as advertisements.

Wei was not the only person affected by such misleading business practices. Hu Shouping, a villager from Zaoyang, Hubei Province, soon came forward to voice concerns that his wife might be this practice’s next victim.

Hu’s wife was diagnosed with stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung in earlier this year.

Doctors at Wuhan Union Hospital had come up with a treatment plan before Hu heard a rumor that chemotherapy could result in leukopenia.

When he searched the web for information on boosting a patient’s white blood cell count, the first result he got was the “CLS biological anti-cancer therapy” offered by Hubei Cancer Hospital.

Hu’s wife went on to have her first course of immunotherapy at Hubei Cancer. Under the original plan, she was scheduled for another course of treatment in May. But when they arrived at the hospital for their appointment, the couple was shocked to see the biological treatment center had disappeared.

The hospital issued an emergency notice dated May 4, saying all its immunotherapy treatments would be terminated and all appointments canceled, promising patients full refunds. After the center was closed, only a few nurses were assigned to manage the disappointed and frightened patients.

“Was our previous treatment effective? Or will it be fatal?” Hu asked the nurses, desperately, but got no answer. This further upset him. “Will she benefit from the closure, or suffer from it?” The hospital claimed on its official website that using CLS therapy either alone or alongside surgery made it effective in killing cancer cells with great precision and in a systematic way when a patient was diagnosed with cancers that had yet to metastasize.

The DC-CIK program, which Wei received, is a leading form of CLS therapy, according to Zhang Lei from the CSB.

Lin Xin, an immunology expert with Tsinghua University, said the overall effects of DC-CIK have not been proven despite data indicating that it showed a certain degree of efficacy in a handful of test patients. The US has conducted studies on the therapy for many years, but the results of almost all related clinical trials have been inconclusive.

DC-CIK is now seldom tested in the US, and no credible research in China has proven any noticeable benefit of using the treatment.

However, the Hubei hospital promoted CLS therapy as a form of fourth-generation cancer treatment technology, claiming that it was “more effective and safe” than surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The hospital claimed it had relieved the pain of over 5,000 cancer patients, and helped them “restore their health.” Since the launch of the CLS therapy program in 2013, it said, more than 90 percent of early-stage cancer patients had been cured, and the five-year survival rate of patients with advanced-stage cancers had more than doubled.

“Even in clinical studies, human beings should not be treated like lab rats,” said Zhang. “Many hospitals have jumped on the bandwagon of the journal Science’s ‘Top 10 Breakthroughs of 2013.’ ” The magazine selected immunotherapy as its top scientific breakthrough of that year.

“This year there was no mistaking the immense promise of cancer immunotherapy,” said Science news editor Tim Appenzeller in a 2013 press statement. “So far, this strategy of harnessing the immune system to attack tumors works only for some cancers and a few patients, so it’s important not to overstate the immediate benefits. But many cancer specialists are convinced that they are seeing the birth of an important new paradigm for cancer treatment.” According to a survey conducted by the China Medicinal Biotech Association from December 2013 to January 2014, 150 medical institutions in 12 provinces and municipalities offered immunotherapy treatment.

To Zhang, that figure underrepresents the craze for immunotherapy in Chinese healthcare.

“Almost all major hospitals have started to run such businesses,” said the CSB council member.

Gray Area The China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) saw a reshuffle of its leadership around 2005, after its ex-head Zheng Xiaoyu was sentenced to death for corruption. The arrest of Wang Guorong, former deputy director of the National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, also shook up its management structure.

The CFDA halted all cell therapy-related programs, resulting in a supervision vacuum.

Previously, immunotherapy products had been subject to the administration’s rules on human cell therapy research and drug quality control issued on March 20, 2003, as well as relevant requirements for market entry.

The sector remained free of official administration until 2009, when the former health ministry issued a rule on the clinical use of medical technologies, which brought immunotherapy back into its supervisory net. But, in 2014, Zhang told our reporter, the National Health and Family Planning Commission (NHFPC) denied it had ever approved the experimental or clinical use of immunotherapy in any medical institution.

According to Zhang, it is easy to start a DC-CIK business: A hospital outsources a department or laboratory to a private entity, which then installs some medical devices. Total investment, he claimed, would not exceed 500,000 yuan (US$76,660). “Many labs claimed they passed the GMP [Good Manufacturing Practice] assessment, which was untrue – setting up a GMP workshop would cost at least 50 million yuan [US$7.7m].” Medical institutions also reaped lucrative returns on their low investments. The abovementioned CMBA survey showed pricing of immunotherapy varied wildly between different hospitals in different areas, with the average course costing patients about 20,000 yuan (US$3,066).

Some patients were given five to 10 courses of therapy, each costing anywhere from 10,000 yuan (US$1,533) to hundreds of thousands of yuan. “Total investment accounted for just one-tenth of the profit,” said Zhang. “The hospital would receive half of this income so long as it recommended the therapy to patients; the subcontractor would take care of the rest of the work.” Another insider said the risk for the hospital lies in potential disputes arising over ineffective treatment or the death of a patient.

“However, cancer patients and their family members often regard doctors’ declarations that something is incurable as a cure to their own economic and mental woes,” said the sources. “Medical institutions have taken advantage of this fatalistic mentality. That’s why immunotherapy has been so popular over the years.” Compared to conventional approaches, immunotherapy appears more “merciful.” “Patients feel like they are in better spirits with this treatment, they eat better and sleep better,” said the insider. “However, many objective indicators showed limited or no improvement at all.” “Even professionals are confused about this sector, not to mention patients,” said He Hongbo, a bone cancer expert at the Xiangya Hospital, Central South University. Moreover, he said “patients who find high medical bills unaffordable have no choice but to turn to cheaper therapies only meant to ease their pain,” as the treatment for many types of malignant tumors, as well as imported drugs, are not typically covered by State health insurance.

Hao Xishan, president of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital and a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, criticized false advertising and the misrepresentation of the efficacy of expensive medical treatments in a profit-motivated healthcare market.

Another expert said a lack of cancer treatment standards invited opportunities for copycat medical technologies to emerge. In 2012, some academics blamed the absence of tumor treatment standards in China for the rising death rate among Chinese cancer patients.

Health authorities have so far worked out standards or guidelines for only a few types of cancers, including colorectal cancer and primary lung cancer, and more effort is needed to cover a wider range.

Craze On May 5, the NHFPC banned the clinical use of cellular immunotherapy as a treatment for cancer following the investigations into Wei’s death.

Zhang Lei said the ban would usher in yet another market reshuffle. Crazes in China for seemingly miraculous medical technology, he said, date back to the 1980s, with the championing of the use of human leukocyte interferons to treat hepatitis B.

“Interferons extracted from human blood taken from patients receiving the therapy demonstrated low antiviral activity, and a high viral load,” Zhang said. This didn’t stop hundreds of small businesses and research institutions from attempting to tap into the market, he continued. Soon afterwards, authorities stepped in to bring the situation under control, with some foreign companies responding to the trend by pulling out of the Chinese market.

Zhang said that government raids on stem cell businesses are the most impressive example of authorities taking it upon themselves to eradicate controversial medical treatments.

In 2012, the health ministry and the CFDA jointly ordered a halt to unapproved clinical research and use of stem cells, curtailing all new programs in the field.

Lack of supervision in this area had been an issue for years. In March 2006, less than a year after its launch, Beike Biotechnology Co., a stem cell tech provider based in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, appeared in a report by the US magazine Newsweek. By taking advantage of murky policy, it was alleged, this medical start-up grew rapidly, along with many others. Incomplete data showed at least 200 companies and institutions were engaged in the stem cell business in China from 2008 to the end of 2011, with some even claiming the ability to cure cerebral palsy, spinal cord injuries, Parkinson’s disease and autism.

With a small investment, a stem cell lab of some 1,000 square meters could generate annual revenue of tens of millions of dollars.

Patients came from around the world to receive these unapproved treatments in China through “stem cell tourism,” derailing legitimate research and testing of what had been a promising new field.

Then, in July 2015, the NHFPC and the CFDA jointly published a new ruling on stem cell clinical research, tightening supervision of the sector. As a result, many investors shifted their focus to the emerging immunotherapy business, Zhang said.

DNA sequencing has been yet another fledgling technology to have its promise undermined by irresponsible and premature deployment by Chinese healthcare businesses over the past few years. “So far, most genetic testing should actually be called ‘genetic fortune-telling,’ which advocates biological determinism but lacks rigorous scientific evidence,” Zhang said. “In fact, most diseases have shown no clear correlations with genes.” The government must learn lessons from the irresponsible development and application of untested medical technology, and try to resolve problems before they develop into healthcare crises, Zhang added.

He Hongbo of Xiangya Hospital, meanwhile, called for a national platform for developing cutting-edge medical technology, alongside an assessment system that gives clear stipulations about how, and when, such technologies may be used.

Old Version

Old Version