Effective use and management of R&D funding have become crucial to determine whether China can transform into an innovation-oriented country by 2020 as Beijing hopes

On April 17, China’s Ministry of Education unveiled a new document on giving scientific and technical research and development (R&D) organs more power to manage their own funding, while pledging to relieve researchers from the burden of the piles of paperwork needed to apply for and reimburse their R&D expenditure.

This is believed to be in response to the 2019 government work report released at the two sessions, China’s annual top legislative meetings held in March, which proposed reducing budgetary restrictions on R&D funding, and setting up what the government called a “contract-based” system. It means that researchers will no longer need to work out detailed budgets to access funds or be banned from spending a penny on any item beyond the budget. Project leaders may freely use the funds as long as they comply with the project contracts and the financial rules of the clients or the entrusting parties.

This new policy has been praised as it is expected to unleash China’s R&D productivity, as researchers will no longer be bound by budget limitations, which, many researchers complained, meant real-world spending could not be covered. Yet, given media reports and supervision departments have exposed that huge amounts of R&D funding have been misused and embezzled, there are fears that loosened oversight will lead to more severe corruption.

The ambivalence was indicated in the latest report on China’s R&D expenditure published by the Faculty of Management and Economics (FME) under Dalian University of Technology, which, for the first time, explained and analyzed how China’s R&D funds were financed, distributed and used from 2000 to 2016. According to the report, China (including government and non-governmental organizations) put in over 1.76 trillion yuan (US$255b) in R&D in 2017, second only to the US in the world. Yet, it does not mean that the funding was used sufficiently and efficiently.

“The major challenge to China’s scientific and technical innovation is not how much we put into R&D, but how we optimize the structure of the inputs and raise efficiency,” Sun Yutao, an FME professor and lead author of the report, told NewsChina, adding that the source and the destination of the funding were the two indicators to appraise the utility of the funding.

R&D Intensity

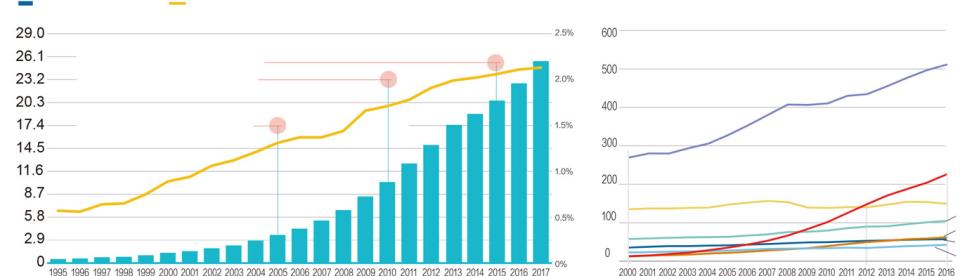

According to the FME report, China has increased its funding of scientific and technical research. Data collected by the FME showed that China’s R&D expenditure has grown year-on-year at an average annual rate of 19.6 percent since 2006, when the government issued a medium- to long-term plan for scientific and technical development (2006-2020). Compared to many developed countries like France, Britain and Germany, such growth was truly fast.

China’s absolute R&D funding has exceeded the above-mentioned countries since 2016, now ranking second in the world. Although it was still less than half of that of the US, it was two times that of Germany, 1.5 times that of Japan, and 1.5 times the total sum of that of Canada, Italy, Britain and France.

However, as for the R&D intensity (R&D expense/GDP), a more convincing index that weighs a country’s emphasis on scientific and technical research and development, it remained below the objective 2.5 percent, a rate that the US has kept above from 2000-2016 and that the Chinese government expected to reach by 2020 – China had issued a strategic plan to make itself an innovation-oriented country by that year.

“It’s pretty difficult for China to reach a 2.5 percent R&D intensity by 2020, let alone the 2.74 percent which the US reached in 2016,” Cheng Ruyan, director of the Center of Policy and Strategy, Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China, wrote in a paper on the comparison of China and US R&D expenditure.

According to Cheng, as the Chinese economy steps into a “New Normal” phase – a term used by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2014 which values economic stabilization and restructuring rather than pure pursuit of fast growth – China’s R&D intensity will not grow at such a fast rate as it did. Data from the FME report showed that from 2000 to 2013, China’s R&D intensity increased from 0.89 percent to 1.99 percent at an average annual rate of 0.085 percent. Yet, from 2013 to 2016, the growth rate dropped to 0.03 percent.

According to Sun, R&D expenditure is crucial to judge if a country is an innovation-oriented country. An R&D intensity of 2 percent is what he believes is the bottom criteria of such a country. Although China’s R&D intensity is lower than the US’s 2.5 percent and the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development)’s average rate of 2.34 percent, it has remained at the 2-percent level for four consecutive years, which, according to Sun, means China deserves to be described as a “half innovation-oriented” country.

Government Input

Sun believes that a harder problem for China is how to keep the rate at 2 percent or above. Despite the continuous growth, China’s R&D intensity has never reached the defined target over past three five-year plans. By 2005, the intensity remained at 1.5 percent, 0.2 percent less than the target set in the 10th five-year plan (2000-2005). During the 11th five year plan (2006-2010), the average intensity reached 1.71 percent, 0.29 percent lower than the target. In the 12th five-year plan (2011-2015), the rate finally exceeded 2 percent, but was still below the targeted 2.2 percent. “It means that China’s scientific and technical input did not match the scale of economic development,” Wan Gang, then minister of the Ministry of Technology, reportedly said at a national science and technology work conference in 2016.

Sun has attributed years of failure to meet the target to the narrowing share of government input. The FME report said that from 1995 to 2016, enterprises became the sole leading source of R&D funding, with the government’s share continuously shrinking. During this period, R&D funding from enterprises rose from 30 billion yuan (US$4.3b) to 1.2 trillion yuan (US$173.9b), a 4,000 percent growth. In the same period, funding from the Chinese government only grew by 12.8 times. Correspondingly, the ratio of enterprise input grew from 30 to 70 percent, while that of the government dropped to around 20 percent.

It was too small a figure compared to data from developed countries. For example, when the US reached a 2-percent R&D intensity, its R&D funding from the government accounted for over 62 percent of the total. A similar ratio also applied to France, Britain and Germany. Although Japan’s government funding was comparatively lower, it took up 27 percent when Japan’s R&D intensity reached 2 percent.

In 2005, Jia Kang, director of the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences under the Ministry of Finance who took charge of the scientific and technical development plan from 2006-2020, pointed out that in an industrialization era, it would be better for the government to keep its R&D input at 30-50 percent of the total, with that from enterprises taking up 40-60 percent. He wrote his expectation into the plan that the Chinese government’s R&D input would gradually increase to 40 percent of the total by 2010 and be stabilized at such a ratio in the next 10 years.

The government, however, went the opposite way. By 2014, the government’s R&D input, according to the FME report, had dropped to 20 percent of the total, much lower than that of developed countries with a similar scientific and technical development level.

“Based on China’s economic development, I think 30 percent is a proper ratio for government input in R&D,” Sun said. He revealed that he and another member of the FME report team have written an article appealing for the government to increase its R&D input to 30 percent by 2020.

‘Startling Corruption’

Besides government policies to encourage enterprises to fund scientific and technical development, Sun believes that a leading reason behind the government’s shrinking ratio lies in the widespread misuse of R&D funds, which has made the government hold an increasingly cautious attitude toward funding.

A survey by the China Association for Science and Technology published in 2011 showed that only 40 percent of China’s R&D funding was used on projects. China’s auditing administration found that in 2010, 99 scientific and technical R&D projects supported by the Ministry of Technology had allegedly misused their funding, with the money in question exceeding one billion yuan (US$145m).

“I am very angry, pained and surprised at the problem,” Wan Gang told media at a press conference in 2013. Under the spotlight, he described the corruption in R&D circles as “startling.”

Things did not significantly improve in the following years. China’s top disciplinary watchdog, the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection, published several articles criticizing the misuse of R&D funds. It said that faking invoices and giving false reports were the most frequent means of embezzlement, which have even become a public secret. Furthermore, in order to

apply for more funding for the next year, many R&D institutions were found to have tried every means to use up the budget at the end of the year, even if a project did not need so much money.

An ironic paradox thus prevailed: on one hand, many scientists and researchers have struggled to find enough money to do research. On the other, a huge amount of money was siphoned off to non-relevant fields or even into individual pockets.

“The rampant corruption was backed by the entire poor management system, including the funding institutions,” Sun said. “For example, the authorities often delayed the fund granting, leading R&D organs to have no money to work on a project in the first half of the year, and in the second half, they had to try hard to use up the money, in case the authorities cut their budget the following year,” he said.

His words were echoed by Wang Jianyu, an academician at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Shanghai Branch. He told media that during the two sessions that the “contract-based” system is more suitable for scientific and technical research, which is often flexible and full of uncertainties.

Similar to Wang, many other scientists and researchers warmly welcomed the reform, but they also called for strengthened supervision and management to prevent and curb corruption, such as enhancing the transparency of each project, setting up a negative list that clarifies the items not applied to the R&D funding, and strengthening the rule of law in the sector. At a press conference on March 11, Wang Zhigang, minister of the Ministry of Science and Technology, pledged that the new “contract-based” system does not mean zero management and control and that more freedom comes with more responsibilities.

Lack of Application

Another big problem lies in the destination of the funding. As revealed by the FME report, China’s R&D input in scientific research, which consists of fundamental esearch and application research, lags far behind that of developed countries.

Data from the FME report showed that from 1995 to 2016, China’s expenditure in fundamental research hovered around 5 percent of the total R&D expense on average. However, that in application research dropped from 26 to 10 percent, with the spending in market-oriented experiments climbing from 69 to 85 percent. The FME report warned that China’s expenditure in scientific research took up only 15 percent of the total, less than half of the US’s when the latter’s R&D intensity reached 2.15 percent in 1957.

The report continued that compared to fundamental research, application research received even less attention, with a ratio far below that of Britain and France, though the latter two countries’ total R&D expense was lower than that of China. Worse, the report found that enterprises, R&D organs and universities had all reduced their input into application research over the past 10 years, with that from enterprises dropping to 3.04 percent from 14.51 percent, that from R&D organs to 28.41 percent from 31.08 percent and that from universities to 49.28 percent from 55.08 percent.

“The low input into application research is highly related to China’s innovation structure,” Sun said. In the US, most application research is done by enterprises and R&D organs, and universities mainly take on fundamental research. In China, both enterprises and R&D organs are scrambling to do market-oriented experiments.

The change, according to Sun, came in 1987 because of the commercialization of R&D organs after the State Council issued two documents on reforming science and technology institutions, encouraging them to enter medium- and large-sized enterprises. Since these new commercial entities no longer received government funding, many had to shift to market-oriented experiments to support themselves.

The report also indicated that universities and R&D organs are doing overlapping and repeated work, and that compared to developed countries like the US, Chinese enterprises have put too little into fundamental and application research, which are actually the basis of product experiments. Data from the OECD, for example, showed that in 2015, Chinese enterprises input US$303 million into fundamental research, 1.5 percent of their American counterparts.

Some Chinese enterprises have started to rethink their attitude after Chinese telecommunication giant ZTE was banned by the American government from buying US-made parts, which led the Chinese public to question why China has no high-quality domestically made chips, although a deal was later worked out. The three-month ban in 2018 nearly crippled the company.

“I’d recommend that scientific research, namely, fundamental and application research, be increased to 30 percent of the total R&D expenditure,” Sun said. “This figure will not happen in the short term, but I believe things will start to turn in the next few years, especially after what happened to ZTE,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version