One morning in late July 2018, 79-year-old Gao Shangquan arrived at his office at the China Society of Economic Reform (CSER) at 8am as usual. In his office packed with books, newspapers and documents, Gao, a prestigious Chinese economist and honorary chairman of the China Society of Economic Reform (CSER) said he was hard at work putting the finishing touches to three books reviewing China’s experiences during its four decades of economic reform. Not feeling the need to slow down, Gao remains active and passionate about his work. He still feels he has a part to play in research that can strengthen reform for the country.

Gao studied at mission schools in Shanghai from primary school, and later worked for multilateral organizations, including the World Bank and the United Nations Committee for Development Policy. It was this personal history that helped him foster independent thinking and enabled him to draw references from foreign countries, he admitted – all experiences that would help him devise sound reform recommendations to help policymakers.

Critical Thinking

Gao started to think about reform back in 1956 when he was working for the First Machinery Industry Department. He noticed even then that State-owned enterprises (SOEs) did not have freedom in decision-making, meaning that senior staff had to ask for approval on certain matters from higher-level ministries. He wrote an article titled “Companies Should Enjoy a Certain Level of Freedom in Decision-Making” which was published in the country’s official mouthpiece the People’s Daily, and this drew the attention of both the government and enterprises. However, due to the political environment of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the inertia of the socialist planned economy at the time, it was impossible to endow companies with more freedom.

Undeterred, Gao maintained his enthusiasm about economic reform. He started to think about the economic problems China faced, especially the deficiencies of the planned economy.

Gao gave NewsChina an example of the waste of resources caused by the planned economy when he worked at the First Machinery Industry Department. There were two neighboring factories in Shenyang, Northeast China’s Liaoning Province. One manufactured transformers; the other was a metallurgical refinery. Both were State-run. The transformer company needed large quantities of copper, and it needed the First Machinery Industry Department to source copper from around China. But the copper produced right next door from the metallurgical refinery had to be distributed by the Ministry of Metallurgy to other places across the country. “This sounds very ridiculous now, but was the reality of that era,” Gao said. “Two factories right next to each other were forced into this bizarre situation because of their affiliation to two different ministries, as well as the lack of a market economy, and it also caused a waste of resources.”

Ice-Breaking Attempts

In 1982, Gao, by then an economic policy researcher, was assigned to the new State Commission for Economic Restructuring. He has focused on reform policies ever since. The same year, the 12th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) was held, after which a sweeping reform of the country’s economic system was announced. During the conference, the “market” was mentioned for the first time in an official CPC document. It pledged to abide by the principle of “ensuring the leading role of the planned economy supplemented by market regulation.” This marked a change from the country’s “mandatory plans” to “guiding plans” and a shake-up of the planned economy, while it also established the foundation for next steps in economic reform.

In early September 1984, dozens of prominent researchers gathered in the Xiyuan Hotel in Beijing’s west to participate in a forum on whether China should start a commodity economy. The forum was initiated and organized by Gao Shangquan and Tong Dalin. Gao was then research group director of the State Commission for Economic Restructuring and president of the China Institute of Economic Systems, while Tong was vice-chairman of the CSER. Before the forum, Gao had advocated writing “commodity economy” into the CPC’s document to be discussed at the National Party Congress, but his suggestion was opposed by conservatives within the Party. Some who opposed the move claimed that they worried about confusing socialism with capitalism, while others disagreed with the mention of a “commodity economy,” only agreeing to mention “commodity production and commodity exchange.”

“I was nobody at that time, and those in opposition were higher ranking officials, so I decided my only option was to find Tong Dalin, and the two of us planned the forum so the issue could be discussed,” Gao said. Participants included prestigious Chinese scholars including Tong Dalin, Dong Fudian and Jiang Yiwei, most of whom, Gao said, were liberal theorists. The forum reached a consensus that a commodity economy was an essential stage for a socialist economy and a report was presented to the central government’s decision makers. It finally resulted in the Party’s adoption of the concept into its strategic documents for economic system reform. On October 20, 1984, a decision on economic restructuring was adopted unanimously by the 12th CPC Central Committee at its third plenary session which highlighted “China’s socialist economy as a market economy based on central planning and public ownership” and pointed out that the“full development of a market-oriented commodity economy was an inevitable step in China’s social and economic development and a prerequisite for economic modernization.”

Former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping lauded the significance of the mention of a “socialist commodity economy” for the first time. “In the past we dared not write this in official documents, since it would be regarded as heresy. We resolved some new problems under new circumstances through our practical experience,” Deng said.

On March 20, 1987, Gao released a report titled “Exploration and Setting up of a Socialist Economic System with Chinese Characteristics,” pointing out the goal of combining a planned economy with market elements should be that the “State regulates the market, and the market guides enterprises.” Then on August 21, Gao published an article addressing the relationship between the planned economy and the market economy, suggesting that an economic contract system should gradually replace the existing national mandatory plan system. The article was noticed by and received written comments from top central government officials. The 13th National Congress of the Communist Party also included Gao’s suggestion into the final report of the congress, stating the mandatory plan should gradually be replaced with an economic contract system, which marked a significant step forward for China’s socialist market economy reform.

The year of 1992 was a turning point for China’s reform. Deng Xiaoping embarked on a still much-discussed Southern Tour, during which he made remarks that propelled economic reform and social progress for the rest of the 1990s. In October that year, the 14th National Congress of the CPC listed setting up a socialist market economy as the final goal for economic reform. In 1993, through his personal efforts, Gao successfully secured support from higher level officials in the central government and had the concept of a “labor market” included in government documents, despite strong opposition. Opponents felt that the introduction of labor into the market would shake the existing dominant status of the working class. Since China’s reform and opening-up started in the late 1970s, Gao helped draft key central government documents six times, including the Report of the 15th National Congress of the CPC and consulted on various central government decisions.

Trudging Ahead

Gao recalled that there were twists and turns as the country evolved from a planned to a market economy at a local level. He cited the experience of Zhucheng, a county in Shandong Province, as a good example.

During the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, many small SOEs were set up in Zhucheng. In April 1992, an audit of 150 city-owned enterprises in Zhucheng found that 103 were missing. New mayor Chen Guang decided a new approach was necessary.

In October 1992, five enterprises were appointed pilot projects for reform, starting with adopting a joint stock cooperative system. Stock in the five companies was sold to employees, despite opposition from conservatives. Cheng Guang was accused of following a capitalist road.

In 1994, Gao Shangquan made a speech on reform of SOEs in Shandong Province, and he was questioned by the audience on whether the reforms in Zhucheng had retained their socialist characteristics.

Gao said he had told the audience that the pilot programs in Zhucheng were necessary, and that he wholeheartedly agreed with the measures taken. He explained that public ownership had stymied the enthusiasm of the workers in those enterprises and therefore reform was urgently needed.

The pilot reform program in Zhucheng continued despite the controversy, and in March 1996, Vice Prime Minister Zhu Rongji headed up a team to Zhucheng to investigate what was happening. He later publicly endorsed the reform attempts.

In 2016, Gao returned to Zhucheng to evaluate the effects of the reform. After visiting a number of local enterprises and noting the differences after 20 years, Gao found that the liquidity of State-owned assets did not result in losses, but instead stimulated the preservation and increase of the enterprise’s value.

Continued Efforts

“The achievements of China’s reform are a result of the socialist market economy,” Gao told NewsChina. He believes that the key to China’s 40 years of reform was marketization, which must be continued. “It was because we stuck to marketization that the enthusiasm of the general public could be sufficiently stimulated,” he said.

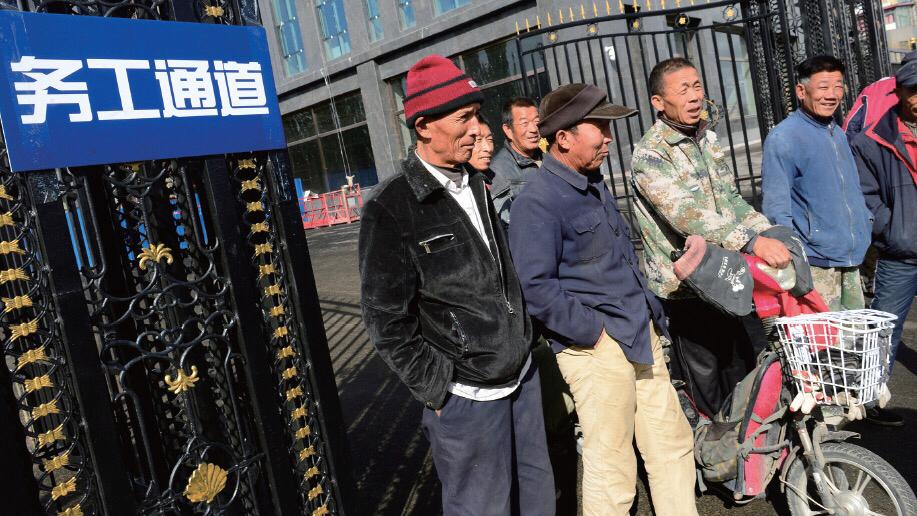

As an economist and reformist, Gao contributed to China’s reform through presenting suggestions to top leaders which resulted in top-down reform policies. In Gao’s opinion, some bottom-up self-motivated attempts such as the household contract responsibility system or the SOE restructuring in Zhucheng were also driving forces of reform. “The grass-roots are most sensitive toward demand from the general public, and we didn’t have an existing roadmap to follow back then, so our efforts were somewhat trial and error,” Gao said. As reform deepened, the bottom-up grass-roots attempts and top-down design integrated and reinforced each other. Gao believes that China’s reform is now facing a more complicated set of obstacles. Key questions include how to make the market play a decisive role in resource distribution and how to create a fair and equal competition environment for firms.

“Reform is endless, and it is a long assignment. As a result, emancipating the mind is also endless which requires continuous innovation of ideas and theories,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version