On March 23, the Beijing municipal government announced it is reducing the maximum amount employers can contribute to work-related injury insurance funds, lowering it from the equivalent of 2 percent of employees’ monthly wages to 1.9 percent. Recently, 11 other provinces and municipalities have issued similar policies that reduce employer contributions to various social insurance funds. Some of them, such as Shanghai and Hangzhou, the capital of Zhejiang Province, took this a step further and reduced employer contributions to pension and medical insurance funds as well. These funds represent the two most sizable chunks of China’s social insurance package; depending on the region, the employer contribution toward these funds per employee is equal to about 30 percent of that employee’s wage.

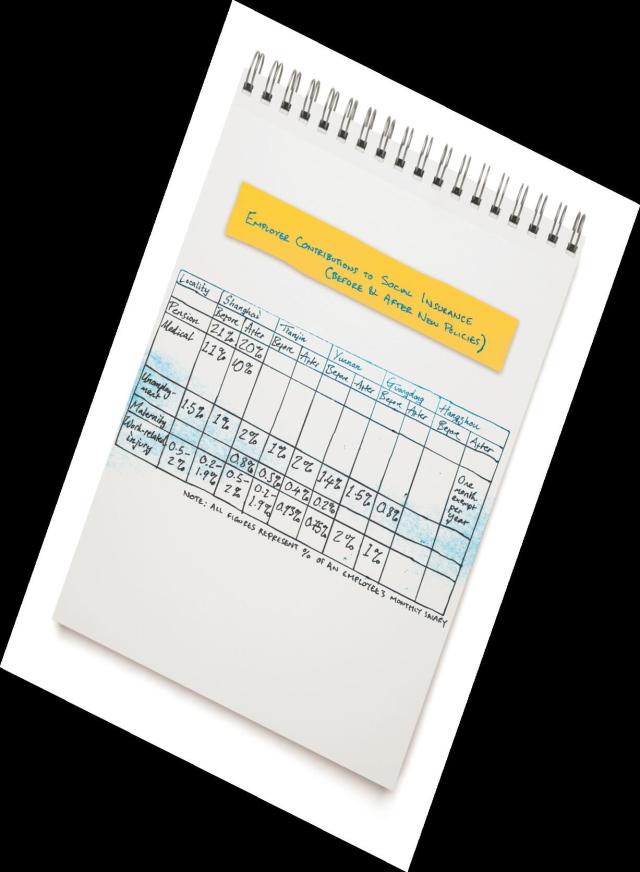

These locally enforced shifts appear to be a response to the central government’s call to lighten companies’ financial loads in order to help lift China’s economy out of stagnation. Currently, social security tacks on as much as an extra 35 percent of employee salaries to businesses’ expense reports. In other words, if employees earn 10,000 yuan (US$1,588) a month, their employers need to pay up to an additional 3,500 yuan (US$556) toward social security funds, split between pensions (20 percent), medical insurance (8-10 percent), work-related injury insurance (0.2-3 percent), unemployment insurance (1 percent), and maternity insurance (0.8-1 percent).

Now that Shanghai and Hangzhou have taken the lead in lowering employer contributions to pension and medical funds, analysts have speculated that more local governments will follow suit. Although officials and business owners hope this move will help pull enterprises out of an economic slump, everyone else views it with trepidation.

While employers are contributing less to pension funds, China’s aging population means an increasing number of retirees are making withdrawals. Current workers worry they will be the ones forced to make up the difference. Unless the government successfully reforms the system, they see only two possible outcomes that will save the country’s diminishing pension funds: either today’s employees will suffer pension cuts when they retire or they will have to work longer because of a raised retirement age, a change the central government has been planning for years.

Small Steps The Chinese government first expressed concern over employers’ insurance burdens back in 2013, during the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Communist Party of China Central Committee, when officials approved a resolution to “properly reduce employers’ social insurance contributions.” The demand was later written into the government’s 13th Five-year Plan (2016-2020). Last year, the central government lowered employer contributions in three categories: unemployment insurance (from 3 percent of monthly income to 2 percent), maternity insurance (from a 1 percent cap to a 0.5 percent cap), and work-related injury insurance (from 1 percent to 0.75 percent). After these changes were announced, accounting expert Ma Jinghao wrote that these maneuvers would help stimulate an economic recovery by enabling enterprises to devote more funds to labor and production.

However, none of these changes touched the two giants in China’s social insurance system: medical insurance and pension funds. The central government’s reductions only represent a maximum of 1.75 percent of an employee’s monthly wage, having “very little effect” on employers’ overall financial burden, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) researcher Tang Jun told NewsChina. Reducing the heftier costs caused by medical insurance and pension contributions would do much more to relieve this pressure, he added.

China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS) has echoed this idea. At a press conference in early 2015, MOHRSS spokesman Li Zhong acknowledged that Chinese enterprises’ contributions to pension funds were “on the high side,” and the amount given to the other four funds (medical insurance, workrelated injury insurance, unemployment insurance and maternity insurance) was significant as well. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang brought up the issue during this year’s annual political meetings known as the Two Sessions, urging local governments to adjust employers’ social security contributions.

The municipality of Chongqing in central China was the first to take action. The local government issued a new policy that allowed small businesses to pay the equivalent of 12 percent of their employees’ wages to pension funds, instead of the previous 20 percent.

Hangzhou and Xiamen, the capital of Fujian Province, subsequently announced they would lower employers’ contributions to medical insurance.

On March 21, the Shanghai government held a press conference on social insurance, announcing it would reduce local employers’ contributions to pension and medical insurance funds by a total of 2 percent, the biggest such adjustment nationwide. “Shanghai employers were paying the equivalent of 35 percent of each employee’s salary toward social security funds, much higher than the employee’s contribution of 10.5 percent,” said deputy mayor Shi Guanghui at the press conference. “Businesses are at the heart of the market economy and the largest contributor to social security, making their stable development a top priority,” he added.

Resistance Although some local governments are pushing forward with these changes, others are pushing back. The reality is that most cities, including Beijing, simply cannot afford to adjust contributions to the pension fund, the biggest piece of the social security pie. With an aging soci- ety and a shrinking workforce, cities are struggling to keep pension funds afloat, according to China University of Political Science and Law professor Hu Jiye. “It really is a hard nut to crack,” he told Ne w s - China.

His words were proven by Zhang Hao, a fund inspector at the MOHRSS.

At a public economic forum held last June in Qingdao, Shandong Province, the official revealed that the amount collected by pension funds in each region has grown at a decreasing rate since 2008, while withdrawals keep rising. Some cities’ funds would already be in the red if not for government subsidies.

“Some regions, like Guangdong and Zhejiang provinces, have saved a relatively high amount [in their pension funds], so they can choose to lower rates,” said Jin Weigang, the MOHRSS’s head of social insurance. “Others that are already dipping into past years’ funds or that need large government subsidies should consider this [cut] carefully.” Workforce Worries While some local governments are hurting, employees worry they are the ones who will really feel the pain. Many are concerned that the general pension funds are already getting shortchanged by greedy employers who purposefully underreport their employees’ salaries in order to pay less toward social security. “I earn 15,000 yuan [US$2,307] per month, but when applying for social security, my employer defined my monthly wage as only 5,000 yuan [US$769],” Gao Bin (pseudonym), a 32-year-old Beijing resident working at an Internet service company, told NewsChina. “[This practice] is quite common throughout the country. It makes me wonder how the government will have enough money to pay my [future] pension when the employers are allowed to give less?” The government is attempting to alleviate workers’ concerns. The MOHRSS has reiterated that the final amount of social security that employees receive has less to do with how much employers contribute over a fixed period of time and more to do with the economic status of the city giving out the pension, as well as the average income level of the local employees. On the surface this seems true. China’s pension payments consist of two parts: the amount originally paid by each individual (received as a lump sum after retirement) and the regular payments that are provided by the local government, not the individual’s employer.

The problem is, of course, that the local government’s funds come straight from local employers.

“Shanghai currently has a surplus in social security funds, including its pension fund, so reduced [employer contribution] rates will not impact pension payments,” read the Shanghai government’s latest document on the issue.

But as China’s demographic problems cause pension fund contributions to dwindle and payouts to multiply, the country’s youth are left in the lurch. If the pensions of current retirees stay stable or increase in coming years (as the government has pledged in the past), people in today’s workforce will face an even more uncertain future.

A safer way to boost pension funds is to increase the number of people paying into the system by raising the retirement age. China’s current retirement age is one of the lowest in the world; men retire at 60 and women retire at either 50 or 55, depending on employment type. The government first proposed this perennially unpopular idea three years ago, triggering a wave of public opposition. During this year’s Two Sessions, the MOHRSS told the media that it will release a detailed plan to increase the retirement age by the end of 2016. The ministry pledged to implement the plan gradually and slowly, but now onlookers are concerned that officials will be given incentives to quicken the process in order to offset decreased pension contributions from employers.

“Reducing businesses’ social security contributions gives them much-needed relief, but the reduction will also lead to a greater pension fund shortfall,” Yang Yansui, director of Tsinghua University’s Research Center of Employment & Social Security, told State broadcaster CCTV. “It is truly a dilemma.” In an online survey about lowering employer contributions to social security on the news website view.news.qq.com, 26 percent of more than 25,000 respondents chose not to support the reduction. “I don’t oppose easing companies’ burdens, since that is good for us employees as well,” posted one netizen following the survey. “But I do not want to pay the final price for it.

I think the government should find other ways to reduce pressure on enterprises.”

Rotten Roots China’s current pension fund system, in which funds come from two sources, individuals and employers, was implemented in 1997.

Before that, China’s pensions were paid directly by employers, many of which were State-owned enterprises (SOEs). In order to reduce the debts of some sluggish SOEs and accumulate funds for the pension payments of a growing number of retirees, the government started to collect money from both employees and employers, separating funds by province or municipality. Each employee’s contribution is kept until he or she retires as an untouched sum, while employer contributions are immediately distributed as pension payments to current retirees. However, given that people who retired before the 1997 reform never paid into the system, the government inflated employers’ contributions to ease initial pension pressure.

“In the 1980s, when Chile was pioneering pension reform, the Chilean government had to sell state-owned copper mines to fill the financial gap caused by the reform,” Hu Jiye said. “The Chinese government, according to some experts who drafted the 1997 reform document, [covered this cost] by raising insurance contributions by several percentage points.” Yet in some regions, employer contributions still do not cover pension expenditures. Poorer areas where large chunks of the workforce have migrated elsewhere are the worst off. Many experts have warned that some desperate local governments have misappropriated individuals’ contributions to pension funds. Instead of leaving them untouched so they can be returned to the worker when he or she retires, some officials have been using those funds to pay current pensions, rendering the 1997 insurance reform ineffective.

In a paper on Chinese social insurance published in 2013, CASS researcher Zheng Bingwen warned that the current system has failed to take China’s aging population into account. There is no mechanism in place to accumulate and save a sum for the growing number of retirees. He said the government should take other measures to reduce the risk of pension fund depletion, such as raising the retirement age and improving economic inequalities between different sectors and regions.

This March, MOHSS minister Yin Weimin revealed that his ministry is designing a new, national social insurance system that will help balance these regional differences and allocate some State-owned capital to help prop up the pension fund. He emphasized, however, that crafting and executing this reform will be a difficult task that requires much coordination and cooperation between SOEs, local governments and various government departments.

CASS researcher Tang Jun agreed that successfully reforming the social security system will be a challenge, but he added that it is the government’s responsibility to meet it. “Right now, the government only spends 8 percent of its budget on social insurance, much lower than the rate in developed countries,” Tang said. “It should spend more.

Old Version

Old Version