It’s late April, and the fresh cucumbers from Guo Chaoming’s greenhouse have already been fully harvested, months before those grown outside are ripe. The cucumbers, grown to organic standards, taste much sweeter than most. 48-year-old Guo is a farmer in Hangjiao, a small town in the mountainous region of Muli County, Sichuan Province, one of the poorest parts of southern China. Inside one of the greenhouses owned by the village cooperative, Guo told

NewsChina that the cooperative’s greenhouses cover a total of 15 mu (10,000 square meters) of land, and house vegetables including cucumbers, cabbages, tomatoes, peppers and watermelons.

The greenhouses were set up in 2014 with over 300,000 yuan (US$44,000) of financial support from the local government of Muli, as part of a nationwide poverty reduction program. The government also spent money on training Guo and other cooperative members in the techniques for greenhouse growing, including drip irrigation.“Since 2015, when we started planting, I’ve been able to earn a net profit of around 60,000 to 70,000 yuan [US$8,000 to $10,300] per year,” said Guo, who also explained that according to the poverty reduction program’s stipulations, his cooperative was required to offer job opportunities to four or five local farmers who were earning below the local poverty line of 3,100 yuan (US$455) a year.

Had it not been for this program, Guo and the other cooperative members would all have remained below the local poverty line. Hangjiao’s poverty is nothing out of the ordinary; there are tens of thousands of towns like it across China. For the current nationwide“Targeted Poverty Alleviation” scheme initiated by China’s President Xi Jinping, the focus has shifted from previous measures to help poor areas to develop economically, to finding sustainable incomes for specific individuals.

New Strategy

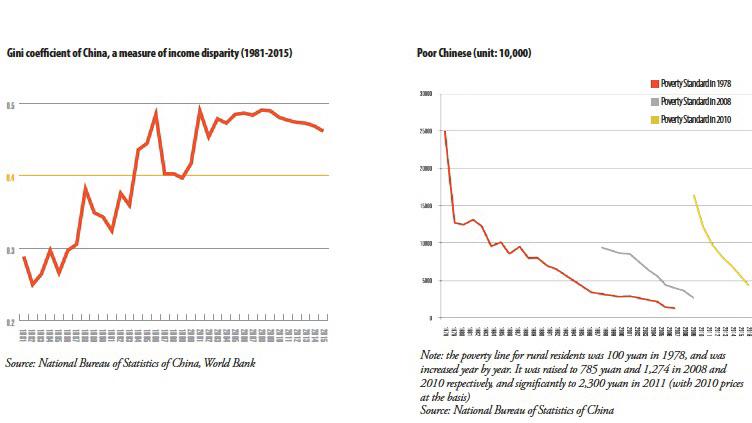

China has been recognized as a model performer in the global poverty-reduction arena. According to international poverty alleviation criteria, which use the measure for absolute poverty as set by the World Bank at US$1.25 per person per day, 660 million Chinese escaped poverty from 1978 to 2010. According to China’s own poverty alleviation criteria, 250 million rural poor were lifted out of poverty over the same period (see chart).

According to The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015 released by the UN, China was recognized by the international community as playing a central role in the global reduction of poverty. “As a result of progress in China, the extreme poverty rate in Eastern Asia has dropped from 61 per cent in 1990 to only 4 per cent in 2015… China alone accounts for almost two thirds of the total reduction in the number of undernourished people in the developing regions since 1990.”

On the latest count in China, in 2012, there were a total of 592 counties and 128,000 villages categorized as “poverty-stricken,” according to its official definition. Most of these were in remote locations with harsh natural conditions and poor public services. Muli in Sichuan Province is one of these impoverished counties.

In 2011, China raised its national poverty line to 2,300 yuan per annum, almost doubling it from 1,274 yuan previously. According to the new poverty line, there were 128 million poverty-stricken rural residents that year. This number had nearly halved to 55.75 million by 2015, within just four years. Infrastructure construction and welfare systems for the poor also saw significant improvements during this period. From 2011 through 2014, according to Liu Yongfu, chief of the Poverty Relief Office of the State Council (PROSC), a total length of some 1.24 million kilometers of road were built to connect poor regions with the outside world. Rural medical services and medical insurance systems were set up. Basic social insurance for the rural population as well as the “subsistence guarantee,” or dibao, the main form of poor relief, have been extended to almost all rural impoverished regions.

The number of poor dwindled significantly due to the country’s three decades of startling economic achievements, yet the last mile of poverty reduction remains the hardest to walk. According to Professor Wang Sangui of the China Anti-Poverty Research Institute, Renmin University of China, in previous poverty alleviation efforts since the 1980s until the early 2010s, the government promoted efforts to target specific regions rather than individual people trapped in poverty.“The regional development model to reduce poverty was reasonable at that stage, considering the overall unfavorable natural conditions in those remote regions which hindered locals’ access to the outside world,” explained Professor Wang to our reporter in June in Beijing.

“However, with the slowing of the national economy and the widening gap between rich and poor, the poor population cannot really enjoy sufficient benefit from overall economic growth, meaning it’s more and more important for the government to provide direct support to poor individuals.”

In response to this new situation, the Chinese government formulated a new poverty alleviation strategy. It was during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to southern China’s Hunan province in November 2013 when he made the first reference to the adoption of “targeted poverty alleviation” measures according to “local conditions.” Then, in 2015, during tours of Yunnan and Guizhou Provinces in southwestern China, Xi further clarified that the key to successful poverty alleviation was to ensure effective help reached those who really needed to be helped. Consequently, “targeted poverty alleviation” became a hot phrase and Party leaders of various levels across the country started to shift greater attention to helping people living in poverty.

Refined Efforts

The new stage in poverty eradication will be more complicated, said Liu Yongfu to China Poverty Alleviation magazine in May 2016, because “most of the remaining poor are people living in the remotest areas without any natural resources or job opportunities.” Additionally, as Liu pointed out, due to low education levels or physical disabilities, they struggle to find work. Statistics released by the government indicate that the main causes of poverty for 42.2 percent of China’s poor were health problems.

The Targeted Poverty Alleviation program targets people through measures including village-level democratic voting, public notifications, and creating a “poor household registry” of every person and household below the poverty line. By 2013, a total of around 89 million people below the official poverty line of 2,300 yuan a year (at 2010 prices) were classified as targets for the new round of the poverty alleviation program. During the past three years, governments at various levels have opened files for each of these 89 million people and the aim is to have no one still under the current line by 2020. Therefore, 10 million people need to be lifted out of poverty annually to achieve the goal of overcoming poverty by 2020.

More specifically, the government at the local level is supposed to draw up new and effective measures for each poor individual. Measures include “Six Precise Items” and the “Five Groups Project.” The former includes precise targets, projects, capital use, measures, specific places and effects. The latter means poverty alleviation through the following five projects: developing poor people’s own productivity, helping the poor migrate to richer places, providing them with ecological compensation (for foregoing economic development for the sake of protecting the local ecology), improving their education, and providing them with social security.

In 2016 alone, government fiscal investment at both the central and provincial level for targeted poverty alleviation programs amounted to over 100 billion yuan (US$15 billion), an increase of over 56 percent on the previous year. Strict annual evaluations of the effectiveness of the program were implemented by the PROSC from 2016 onward, which ensures governments’ active and qualified participation at the local level and helps avoid corruption.

Huang Xuyou, director of Muli County’s poverty alleviation office told our reporter that with the direct financial and technical support provided by the government, even the remotest village can develop cultivation of its own agricultural produce such as black fungus, toadstools or medicinal citron. “With strong government investment, farmers can realize sustainable development opportunities through the cultivation of relevant agriculture products,” said Huang, acknowledging that poverty alleviation efforts saw particular progress in the last two years in Muli.

Global Vision

The overall scheme of China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation program with its accompanying theories and practical measures can be promoted globally for the purpose of poverty reduction. Professor Wang commented that the scale and effects of the program so far are unprecedented globally.

“Global statistics about populations living in poverty released by the World Bank are mostly abstract numbers, but data on people in precise locations is hard to discover,” Wang Dayang, head of the social mobilization department of the PROSC told NewsChina, “While income level is only one indicator used to define poverty, a number of other variables such as health conditions are also important.” Despite the difficulty in clarifying and distinguishing the genuinely poor from the merely hard-up, China is making bold efforts at a tough mission.

With top-down dedication and sufficient monetary backup, at current rates of reduction, it should not be an issue for China to meet its target by 2020. Yet an often overlooked reality is that since the 1980s, income disparities in China have widened rapidly, with China’s official measure of the Gini coefficient used to measure inequality reaching 0.469 in 2014, high by global standards. Research by others put the figure for the measure higher still. Thus poverty alleviation as a way of narrowing disparity will still remain a long-term task for the Chinese government.

According to Wang Dayang, the current efforts are aimed only at extreme poverty in the countryside. “The poverty line will be adjusted after 2020, and more likely, ‘comparative poverty’ will be adopted as the criterion for defining poverty by then, rather than the controversial income level,” Wang explained, saying that, for example, poverty might be defined by differently in eastern, central and western China. Urban poverty is another constant problem haunting China.

“Who are the urban poor, how do we define them in a more realistic way, and what kind of poverty alleviation efforts measures could be taken among these populations? These are important topics for researchers to consider in the near future,” said Wang to NewsChina,“One thing’s for sure, the year 2020 will not be the end of poverty in China.”

Old Version

Old Version