Old Version

Old Version

In the spring of 2016, when Wei Shuanbing, a villager in northern China, was working on his family cornfield, an adult leopard jumped down from the slope of a nearby mountain, padded across the road, and ambled up the slope of the base of the next mountain. “A couple of other villagers were around, and we all saw the leopard at that exact moment,” recalled Wei to NewsChina in mid-May. Heshun county is near Jinzhong City in China’s northern Shanxi Province, some 400 kilometers southwest of Beijing.

Wei and fellow villager Er Bao met another leopard a few days before, in the mountain forest. There had been no sightings of leopards by locals for the past two decades. The personal encounter of the big cat reminds Wei of his almost forgotten teenage memories, before the mid-1980s, when it was common for him to spot leopards in the surrounding mountains. “The leopards were not afraid of humans and they never ever attacked humans as far as I know,” Wei told our reporter during a recent telephone interview, “In most cases, they would walk away indifferently when I met them.”

Since the late 1980s, due to various reasons including deforestation, road construction, coal mining activities in the Taihang Mountain range in Shanxi, as well as poaching, the number of leopards fell sharply. Wei said that since 2000 he hadn’t seen any leopards until this year.

Thanks to the country’s national Natural Forest Conservation Program launched in 2000 and the confiscation of privately-owned rifles from the late 1990s, the North China Leopard, a subspecies of the leopard family, very slowly clawed its way back. “There are no reliable statistics yet indicating how many leopards there are in Shanxi,” Song Dazhao of the Chinese Felid Conservation Alliance (CFCA), a domestic big cat conservation NGO, told NewsChina in May.

“Locals in Heshun can generally live quite peacefully with wildlife, and they do not feel frightened if they see a leopard nearby,” Song said to the reporter, explaining that the area’s comparatively hospitable natural environment and sufficient prey also contributed to the revival of leopard numbers.

The North China leopard, confusingly categorized as Panthera pardus japonensis, is a subspecies of the Panthera family. The name comes from zoologist John Edward Gray who was working at the British Museum and based it on a leopard skin obtained from Japan in 1862.

However, the skin originally came from Beijing and subsequent studies proved it was from a leopard that lived in a northwestern mountain area outside the city.

Historically, the mountain ranges surrounding Beijing, accounting for over 60 percent of the city’s current territory, were major habitats of the North China leopard. Rapid urbanization and increasing human interventions during the process saw the species disappear from the region in the 1990s.

Leopards are widely distributed across Africa and Asia, but populations have become reduced and isolated, and they have been driven from large portions of their historic range. According to the most recent assessment of the species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), evidence suggests that leopard populations have been “dramatically reduced due to continued persecution with increased human populations, increased illegal wildlife trade, excessive harvesting for ceremonial use of skins, prey base declines and poorly managed trophy hunting” and “suitable leopard range has been reduced by over 30 percent worldwide in the last three generations (22.3 years).” The leopard in general is listed as “vulnerable” on the IUCN Redlist.

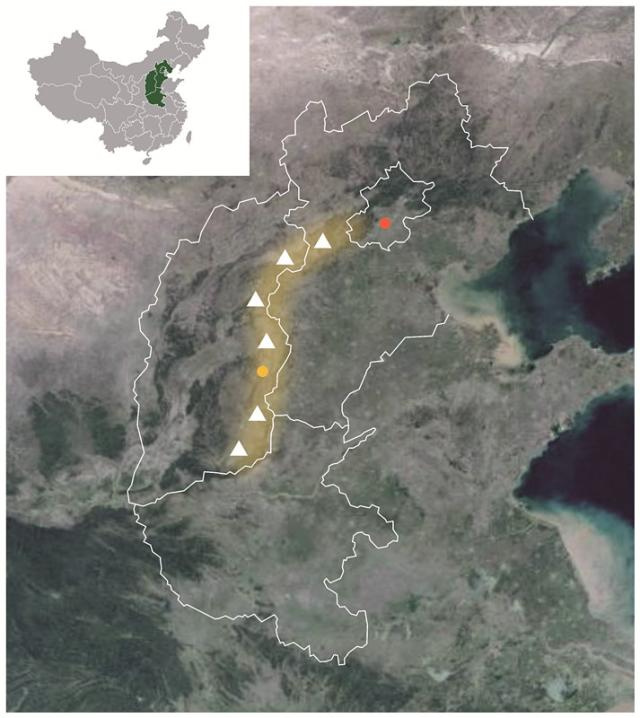

The Taihang Mountain range expands in a north-south direction from Beijing to Hebei and Shanxi Provinces, then further south to Henan Province and touches on the Qinling Mountain range in Shaanxi Province. In recent decades as the natural corridors of mountain forest areas have been blocked due to newly-built roads and villages, or given over to agriculture, the habitat of the leopard in northern China has shrunk dramatically. Prey species of the leopard, including wild boar (Sus scrofa) and the Siberian roe (Capreolus pygargus), once populous inside these mountain ranges are increasingly under threat from illegal hunters’ wire loop traps, iron hunter traps and electrified wire netting, leading to collapses in prey populations across the whole region. Since 2000, according to the CFCA, there has been no recorded sighting of a leopard in the Beijing region.

In the winter of 2012, a camera trap installed in Xiao Wutai National Reserve in Hebei Province captured a glimpse of a leopard. This was the closest position to Beijing for a decade. According to Song Dazhao, the CFCA has attempted investigations and research in Beijing’s mountain ranges for years but so far no leopard has been spotted. “The biggest problem is the lack of prey to support a healthy breeding population of leopards,” Song told NewsChina.

Based on images collected through some 100 camera traps across an overall area of nearly 300 square kilometers in Shanxi since 2013, Song Dazhao told NewsChina, so far a total of around 15 to 18 adult leopards have been recorded. This population is proving fairly stable and is breeding in the area. Song also acknowledged that no study has been conducted so far on how young leopards migrate to other places after they mature, and that they are considering using radio tracking for further study. “What we can assure for now is the safety of the leopard population within the area under our monitoring, but we cannot assure their safety when they move out of the area,” added Song.

In 2016, a 100MW wind power project was planned by the local authority of Heshun county in the Taihang Mountain range. If it gets the go ahead, the project will destroy the natural habitat of the leopard as a proposed road of 100 kilometers would be constructed along the mountain slope. The CFCA and a couple of other environmental NGOs have issued a joint petition to the local government to change the project location to avoid the potentially lethal impact on the leopards. So far negotiations have gone smoothly and this May, Sun Yongsheng, the party secretary of Heshun County, announced on a local television channel that construction plans for the project had been adjusted to make way for the movement of the leopards.

The raising of beef cattle has historically been a pillar industry in Heshun and almost all households in Mafang town – the focus of the CFCA’s conservation project – have raised cattle on the nearby mountain as major source of income. Normally, villagers would let their cattle freely roam the mountain and check on their livestock once every week or two.

With the recovery of leopard numbers, there have been frequent attacks by leopards on calves or adult cattle, causing significant financial impact on local villagers. The market price for a calf is around 5,000 to 6,000 yuan (US$725 to $870) and for adult cattle, over 10,000 yuan (US$1,449) a head – a significant amount in a poor rural area where villager’s annual average income is just 10,000 yuan (US$1,449)

This directly results in retaliation by local villagers towards the leopard that killed their cattle. Despite the leopard’s listing as a first class national level protected animal, whose killing is punishable with a prison term, villagers secretly conduct the killing through poisoning. Leopards have the habit of coming back a few times to eat their unfinished prey, which allows villagers to inject poison into the cattle’s corpse. “Cases of leopards attacking cattle often take place in spring when calves are newly born. It used to be very common for locals to carry out retaliatory poisoning when their calves were killed by leopards within the region,” recounted Song to NewsChina.

Since 2015, to alleviate the human-carnivore conflict in the region, the CFCA started to try compensation for local villagers who lost cattle to leopard attacks. The compensation was set at 2,000 yuan (US$290) per head of adult cattle and 1,000 yuan (US$145) for a calf. According to Song, in that year alone, a total of 70,000 yuan (US$ 10,149) was spent on compensation for the deaths of 48 cattle in that particular town. In 2016, with financial support from the local Heshun government and SEE Conservation Fund (Society, Entrepreneur, Ecology), the CFCA initiated a larger program called “Buy Me a Steak.” The program aimed to raise money for compensation for village households who lost livestock to leopards in the mountain area. In 2016, a total of 40,000 yuan (US$5,800) was issued in compensation for leopard attacks.

In the meantime, a local volunteer group named “Old Leopard Team” composed of five villagers from Mafang was set up by the CFCA in 2015 to assist with on-site conservation efforts as well as evaluating damage caused by leopard attacks. Wei Shuanbing is a member of the team.

According to Wei, once a month, the team heads into the mountain area, checking camera traps of wildlife images or spotting illegal poaching activities. The CFCA pays each member a monthly salary of 500 yuan (US$72.50). The team has set up a direct reporting channel with the local nature reserve and forestry bureau as well as township government, thus once any illegal activity is spotted, a team member can call forestry police to attend.

Through years of efforts, the CFCA has identified almost 20 individual leopards through hundreds of images captured by camera traps around Heshun. The local Shanxi government is also very enthusiastic about setting up a scientific database for the research of leopards in the province, so as to upgrade the area to a national nature reserve with better financial and academic support in the long term. Shanxi Provincial Forestry Bureau has invited academics to conduct a study of the leopard population in certain areas and, so far, camera traps have been installed in a much wider region that covers 15 nature reserves in the province.

Fortunately, the preliminary study results indicate that the leopard population in Shanxi remains stable.

However, the positive trajectory might be temporary and any policy changes could result in an end to the remaining leopard population. Shanxi is famous for its rich coal resources. Mafang town in particular, according to Fan Xinguo, a local official, has been included on the list of the country’s strategic coal reserve areas for its huge amount of surface coal. “Once the coal mining industry starts off someday, the environment will be completely ruined,” said Fan to Sanlian Lifeweek in May 2016. If the protection efforts are in vain, the leopard’s last habitat would fast disappear.

The primary obstacle for the preservation of the North China leopard lies in insufficient study of the species inside China. China has cultivated a sound basis of public wildlife protection awareness for some more “charismatic” species such as the giant panda or Amur (Siberian) tiger. However, public recognition for the leopard in general in China is a completely different picture.

The on-going pilot project of China’s Amur tiger and Leopard National Park in northeastern China aims to maintain the integrity of the habitat. The two species’ situation is similar, and so avoiding the fragmentation of its habitat, and restricting industrial development is crucial. “The harmony of the coexistence of humans and wildlife requires human interference to be within certain levels,” said Song Dazhao to Beijing Science and Technology News during an interview in September 2016: “research has indicated that when the area of farmland exceeds a certain level inside the habitat, the tiger will not live there.”

This April, the CFCA launched a new program called “Bring Leopards Home,” aiming to restore the continuity of natural habitat along the Taihang Mountain range, rewilding it for the leopards and allowing their free movement along the whole range. The ideal picture, according to Song, is where a leopard can roam freely along the Taihang Mountain range from Shanxi to Beijing, or south to Henan and Shaanxi.

Researcher Liu Yanlin of the Chinese Academy of Forestry, who focuses on snow leopard conservation told NewsChina recently that case studies from India and South Africa have proved that leopards can survive in areas densely populated by humans. The Taihang Mountain range is one of the best-protected regions in northern China, he says, and the comparative scarcity of human settlement in the range allows a high possibility for ecological recovery. “The biggest two challenges ahead are whether illegal poaching can be contained in the Taihang Mountain region, and whether construction work including road and real estate development can be soundly planned. The results all depend on the attitude of the local government and general public towards the preservation of this subspecies,” Liu remarked. “The Taihang Mountain range could and should be the last wilderness for the North China leopard.”

For decades, wildlife preservation methods in China have focused on two aspects: one is the mainstream preservation of existing habitats, for example the cases of the giant panda, snow leopard and Amur tiger. Second, the recovery of some species with small populations in a limited area, such as the successful revival of the Asian crested ibis. In Liu’s opinion, the CFCA’s plan of “Bring Leopards Home” is very ambitious in recovering the Chinese leopard population across a wider range of its historical distribution area.

“If the goal could be reached by joint efforts of the government and the public, it could be viewed as a milestone in China’s wildlife preservation history,” Liu concluded.