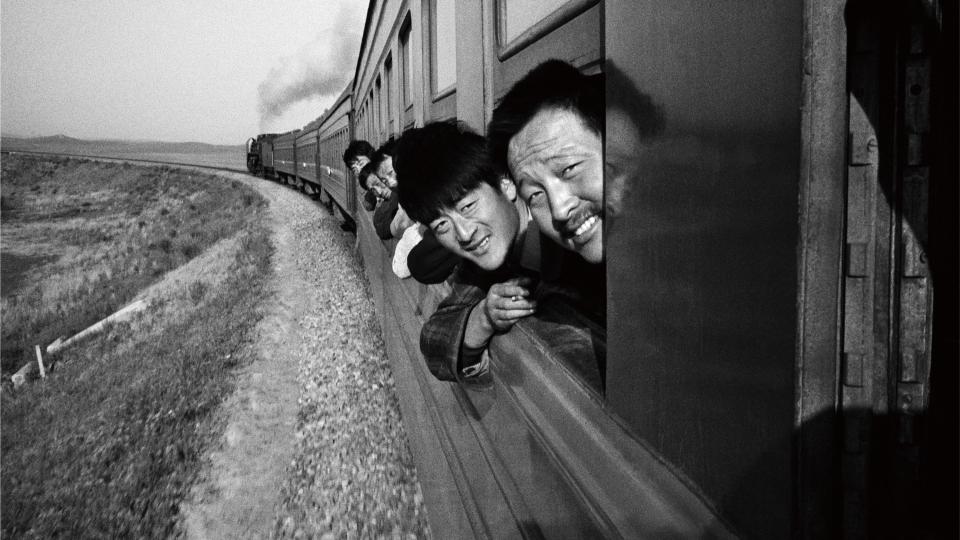

“The railway carriage is a microcosm of society. All walks of life and every aspect of Chinese living are squeezed into this small space,” said 73-year-old Wang Fuchun.

Since 1977, Wang, a famous documentary photographer, has dedicated himself to photographing a particular subject – people on trains. Funny, tender and nostalgic, his black and white images vividly demonstrate numerous intimate moments of ordinary Chinese people on long journeys.

“Trains are loaded with stories of hope, happiness, regret and pain,” said Wang. From steam locomotives to bullet trains, the photographer has captured the trials and tribulations of ordinary Chinese, as well as China’s modernization and social changes since reform and opening up began in 1978.

Photographing Railways

Born in 1943, Wang is a native of Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, northeast China, where Russian and Japanese-built railways have long made it one of the most connected parts of China. Wang, whose parents died when he was very young, was raised by his elder brother, a railway worker, and his sister-in-law. He grew up near railway tracks and dreamt of becoming a railway driver in the future.

But the rails weren’t Wang’s only passion - there was also art. He joined the army in 1965 and spent five years drawing reverential portraits of Chairman Mao and comics about the exemplary deeds of model workers or soldiers, as was typical for the time. Wang left the army in 1970 and was hired by the propaganda department (later the publicity department) of the trade union under the Harbin Railway Bureau.

Wang’s journey of photography started in 1977, shortly after the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when he was asked to take photographs of model workers on the railways. He borrowed a Shanghai Seagull camera from the technology office, one of the few models available in China at the time. “Once I took up the camera, it was hard to put it down. I always say that I took off with a Seagull and I’m still flying today,” Wang told NewsChina.

Wang commuted by train every day, which allowed him to observe passengers in the carriages and snap moments. Before the term “documentary photography” was introduced in the Chinese mainland in 1995, Wang had already unknowingly practiced it since the late 1970s.

He became a professional photographer in 1986 as he was transferred to an institute under the Harbin Railway Bureau. The new post provided him greater resources such as film, equipment and also a railway pass that allowed him to travel all around China free of charge.

With his free pass, Wang has journeyed to every bit of China the railways touch. Since 1977, one year before Reform and Opening Up officially began, he has taken thousands of trains, traveled more than 130,000 miles and used over 100,000 rolls of film.

His passion has also got him into trouble on numerous occasions.

The most dangerous experience he had was on the Harbin-Shanghai express in 1991. He nearly fell onto the tracks when he caught hold of the door handle but failed to enter the train as the door suddenly closed. “I gripped the handles as hard as I could. But the train accelerated and my body started to be lifted up. At that critical moment, the door opened and the conductor and some passengers dragged me into the car. I collapsed and couldn’t stand up for quite a long time. That near-death experience was one of my worst nightmares. Even today I quiver at the thought of it,” Wang told NewsChina.

He spent so much time on trains that in the early 1990s Wang couldn’t fall asleep without hearing the clanking sound of rail tracks. “When I was at home, I took five or six sleeping pills but it didn’t work. Strangely, when getting on a train, I fell asleep as soon as I lay down. The locomotive screeched and clattered, sounding like a symphony or a lullaby,” said Wang.

He believes that acting without his subjects’ permission is the only way to capture reality. Wang describes his shooting as “undercover photography” and jokingly calls himself a “thief.” “I do not steal their property but their images,” said the photographer. Walking back and forth through the packed carriages and snooping around here and there, Wang silently snaps the little moments with an unnoticeably small camera.

Nowadays people are much more sensitive about privacy issues and image rights, which makes it harder for Wang to take photographs. “It’s lucky if I am just told to delete the photos. More often than not, what waits for me is abuse, punches and kicks. I am always reported to the railway police by passengers suspicious that I am a thief,” Wang told NewsChina. Last year, Wang was beaten by a man who objected to his baby being photographed.

In 1998, Wang retired from Harbin Railway Bureau and became a freelance photographer. In 2000, his “Chinese on the Train” series was exhibited in the Denmark IMAGE Festival. One year later, in 2001, the photographer published the album Chinese on the Train.

Wang has won the 17th National Film Festival gold medal in China, 3rd place in the Chinese Photographic Art Award, and has been named an outstanding photographer. His works have been widely exhibited around the globe, including in the US, Denmark, the Netherlands, France, Brazil, Italy, Britain and Russia.

Wang has also explored many other photographic projects, including “Steam Locomotives in China,” “Black Earth,” “Siberian Tigers,” and “Households in Northeastern China.” But life on the trains is his real passion.

He is now 73 and still taking photographs on trains. “It’s really rare for a photographer to spend 40 years on a single project,” said Wang. “It’s like digging a well. Many photographers don’t have the patience to dig deep enough into their projects and just walk away to attempt something new. I’ve dug the well for four decades and the water I’ve found is so sweet and rewarding.”

Wang told NewsChina that in 2018, the 40th anniversary of the reform and opening up, he will publish two albums, 40 Years of Chinese on Trains, and 40 Years of Chinese Images.

A Small Society

In Wang’s eyes, a train is like a mobile society or a temporary family. On the train, all aspects of Chinese society can be found in small compartments. He creates intimate portraits of the diversity of Chinese society: men and woman, young and old, of a variety of ethnicities and religions.

“I’ve witnessed too much all these years. I’ve captured lots of beautiful moments but also seen too many crimes under on board, such as drugs, prostitution and theft. Everything, bright and dark, good and evil, that happens outside happens in the carriage,” Wang told NewsChina.

Wang often bumps into thieves on the train. He joked that he can spot a thief better than the railway police can. “Sometimes I stare at a pickpocket and he gazes back at me. He thinks I am a thief, but actually he is the true one,” Wang grinned.

Through decades of practice, Wang has developed an acute sense of the best way to catch the emotional subtlety and revealing details in everyday scenes on the railway.

One of Wang’s most widely reproduced work was taken in 1996 on the Guangzhou-Chengdu express. In the picture, a pair of young lovebirds cuddle in a small single bunk and stare affectionately at each other, with a blanket covering their bodies. The lovers, Wang explained, left their hometown in Sichuan Province, and, like hundreds of thousands of people in the 1990s, they headed south to Shenzhen to find work. Shenzhen was one of the pioneers of Reform and Opening Up, a promising new land of chance and hope.

“We all know that boys and girls from Sichuan are notably bold and open. When the young couple noticed my camera, they immediately covered their heads with the blanket and playfully kissed hard and noisily. Everyone around laughed. When they threw off the blanket, I pressed the shutter. So came the wonderful photo,” Wang told NewsChina.

The photo Wang loves the most was taken in 1998 on the train from Qiqihar to Beijing. In it, a bright-eyed Buddhist master in his 80s dons a pair of gloves to feel the pulse of a young female passenger.

“The white glove is the highlight. When the girl asked him to check her pulse, the old master took out a pair of gloves from his robe and put them on. According to the Buddhist rules of etiquette, it is improper for unmarried men and women to touch each other’s skin. I felt so lucky that I could capture such great detail,” said Wang.

Wang believes that a photographer needs to have empathy with his subjects so that his works can resonate with the viewer.

In July 1995 on an extremely overloaded train to Nanjing, Wang saw a 5-year-old bare chested girl standing asleep against the train door, her body covered in dirt and sweat and her head nodding slightly. “It pained me when I saw her standing there sleeping. I blamed myself for not being able to offer her any help. I watched her for five minutes but couldn’t force my fingers to press the shutter. My heart ached at the moment when I eventually took the picture. It reminded me of my parentless childhood. I saw myself in her,” Wang told NewsChina.

Snapping History

In Wang’s eyes, documentary photography is a study of humanity. In his earlier years, Wang spent much time on many other photographic projects such as “Steam Locomotives in China,” “Black Earth” and “Siberian Tigers.” But his real subject has always been humanity.

“I’ve photographed Siberian tigers for 20 years but the animals always look the same. They never change. But people are different. Their way of dressing, thinking and behaving has changed tremendously with the passage of time,” Wang said.

His photos faithfully record the changing fashion trends over the four decades. At the end of the 1970s, almost everyone wore the same things: green military clothes and hats, a badge with Chairman Mao’s portrait on it, and a green army canvas satchel; in the 1980s, lots of novel things popped up – hair-dyeing, flared jeans, tight pants and stockings; in the 1990s, printed T-shirts came into fashion as a way of individual expression.

Many once trendy but outdated symbols have been preserved in his lens – flip phones, beepers, Walkmans, cassettes of Teresa Teng (Teng Li-chun), a renowned singer from Taiwan who was popular on the Chinese mainland in the 1980s and 1990s and once banned by the authority for several years as too “bourgeois” and “decadent.”

In the era of slow trains, Wang described railway journeys as an uncomfortable and even painful experience. In the late 1980s and early 1990s in particular, the trains used to be exceedingly packed, especially during the Chinese New Year holiday rush, which has been described as the biggest human migration on the planet. Wang’s albums include scenes of people clambering into carriages through windows, lying under the seats or above the baggage racks, or standing inside the toilets or in the aisles for days and nights on end.

In 2006, China’s railways underwent a major upgrade with the introduction of high-speed trains. The country now has 11,800 miles of high-speed railways. According to China National Television, by 2020, China will have 93,200 miles of railway tracks including 18,640 miles for its bullet trains.

Wang describes modern trains as “mobile grand hotels” and “flights on land,” which enable passengers to enjoy faster and more comfortable and convenient journeys. But he still misses the old days on the stuffy slow trains when passengers would chew the fat and make friends with strangers. In his words, “lots of stories might happen.”

Wang says that today people on the modern bullet trains and high-speed railways are all engrossed in their smartphones, iPads and laptops. “When I walk back and forth through the carriages, everyone, male and female, young and old, buries their noses in the little gadgets in their hands. There is almost no story to be found,” Wang said.

Wang attaches great importance to the historic and documentary value of photography. He believes documentary photography should be a realistic, vivid and a profound record of life, society and history.

“I am not a journalist. It’s not my area to depict a grand narrative or big picture of national events. As a photographer, I see it my responsibility to record the life of ordinary people, to capture those visible but ignored everyday scenes. I feel really lucky to have been able to photograph people on trains and provide a perspective to peep into the changing Chinese society,” Wang told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version