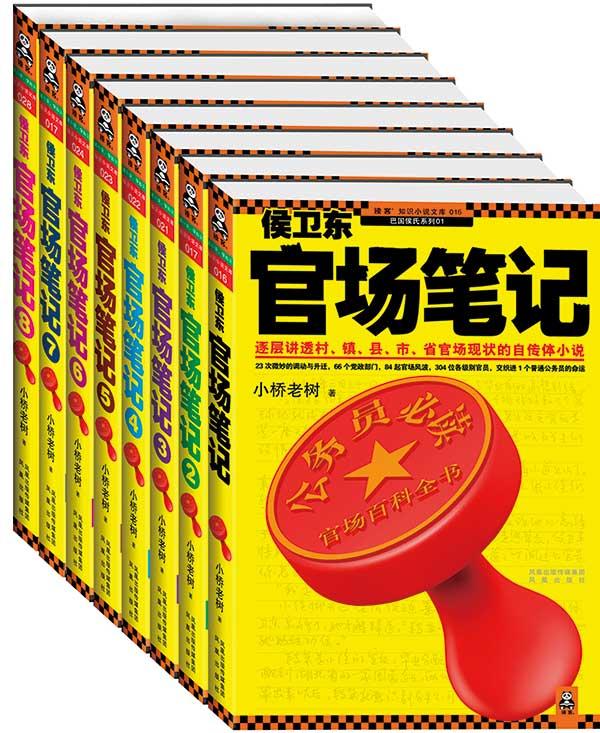

While the author’s name is more or less unknown to Chinese people, Zhang Bing’s The Diary of Government Official Hou Weidong series of novels, published in installments online, is known nationwide for telling the tale of scores of incidents involving hundreds of fictional officials. The novels are so realistic that some critics have praised the series as having “unveiled the deepest truths and secrets of officialdom.”

To date, Zhang, under the pen name “Xiaoqiao Laoshu” (literally: small bridge, old tree), has published eight volumes of the saga, in which he tells how the leading character, Hou Weidong, is promoted step-by-step from village official to city-level official, thanks to his ability to deal with government affairs and keep a well-connected network of connections (guanxi in Chinese). Over the past year, however, Zhang has slowed down the pace of releasing chapters. During this period, many impatient readers have helped continue writing the series online, but none of the endings, Zhang said, conforms to his ideas for his creation.

According to Zhang, he originally planned to promote Hou to a provincial official, but as he himself only reached the lowest county-level official, he worried that he could not truly depict the work and lives of higher-level officials. Furthermore, as Zhang entered his forties, his outlook on life began to change, and he hoped that Hou could also slow down his pace and rethink his life. It may go against what readers have come to expect, but Zhang said that the novel reflects both his and Hou’s lives.

Rapid Promotion

In the first volume, Hou Weidong graduates in 1993 and is selected by the local organization department (the government organ in charge of the personnel arrangements of local officials) as one of the graduate officials working at village level. As a college leaver Hou is full of vigor and hope for the future.

This is Zhang Bing’s own story. He graduated from Chongqing University of Arts and Science in 1995, passed the organization department’s selection and was appointed as one of the village officials out in a local town on the fringes of Chongqing after six months’ study at the local cadre-training school.

However, as happens to Hou in the novel, the village Zhang was sent to was so backwards and poor that it threw cold water on Zhang’s dreams. Worse still, the parents of Zhang’s girlfriend did not allow the pair to marry due to his lowly position. Young Zhang then set his mind to get back to the city under his own steam.

“I promise that I will get promoted back to the city within three years,” Hou tells his potential mother-in-law in the novel. Zhang made a similar promise in the real world. Although he did not give himself a time limit, it became his dream to get promoted as quickly as possible.

Driven by the promise, Hou works harder than any of the other village officials. The poverty of the village provides Hou with plenty of scope for development. He experiences a series of tough, grinding government affairs, from building village roads to dealing with serious industrial accidents, from family planning to funeral and interment reform. Through Hou’s experience – in actual fact Zhang’s real-life experience – Zhang paints a picture of how, under Deng Xiaoping’s direction, rural parts of China were heading toward a market economy and opening their minds.

Thanks to the notes Zhang kept when he served as an official, he has been able to detail many specific affairs and incidents in his novels. For example, how they persuaded a pregnant woman who had violated the one-child policy to have an abortion, and how they publicized and forced cremation in the village where residents still believed that burial was a sign of respect to the dead. The details are so vivid and real that many readers on douban.com, China’s most popular bulletin board for arts and literature, commented that Hou’s experience as an official in a village is highly engaging and stands out from other works of officialdom fiction.

Through his constant hard work, Hou gained a good reputation in the village and was elected deputy town mayor three years later, despite not being nominated by any of his higher-ups. One year later, he was promoted to secretary to the Party Secretary of the local county (counties are two ranks higher than villages in China). Given that Party Secretary is the top position in a county, Hou’s own position made it much easier for him to keep getting promoted.

Over a similar time span in the real world, Zhang Bing was promoted to town-level armed forces director (the Communist Party of China maintains armed forces departments in most counties and towns to manage militia-related affairs). He was 28 years old, the youngest armed forces director in the area. Three years later, Zhang was sent to work at the district-level politics and law committee, an important local department in charge of legal and public security-related affairs.

Career Change

Despite quick promotion, Zhang faced financial hardship in 2006 when he had a daughter. In order to be together with Zhang, his wife left her job and moved to the city with him to go into business. However, she suffered great losses, and Zhang, whose monthly wage was a mere 1,600 yuan (US$200 at the time), had to support the family alone.

“Down and out” is how Zhang described his life at that point, but he told NewsChina that he naturally rejected corruption, the typical way for many officials to supplement their salaries. In his childhood, he witnessed how a corrupt, fallen official was looked down upon by those around him, even the children, and did not want to be that same person.

Since he majored in Chinese literature at university, a recruitment advertisement for online writers caught Zhang’s eye one day in 2006, just as online literature was beginning to emerge as an industry. Zhang had seldom picked up his pen since joining the local politics and law committee, let alone writing novels, but he decided to try the new job as it did not violate the regulations for officials – the government does not allow any official to go into business.

Zhang’s first novel was historical fiction and he finally earned a 5,000-yuan (US$650) contribution fee, three times his monthly wage. Spurred on by the money, he immediately began planning his second novel.

At that time, Zhang had been promoted to deputy director of the local parks and landscape administration and his financial worries had largely eased. This prompted him to write about how a man grows up and works his way up, using the officialdom with which he was so familiar as the background.

It was a very risky choice, since by then, there was almost nothing in the way of fiction about officialdom, except for several historical works. Zhang recalled that The Diary of Government Official Hou Weidong was only China’s second realistic novel about officialdom. To be politically safer, Zhang set the novel in the 1990s, a time when China achieved startling development under the policy of Reform and Opening-up and in which Zhang was fighting to achieve his dreams too.

Realism The novels’ protagonist, Hou Weidong, takes an entirely different path to his creator. When still a village official, Hou eschews poverty and becomes a millionaire by operating two quarries – in his mother’s name.

Not going into business was Zhang’s real-life regret. He told NewsChina that the village where he was working had abundant stone resources, but he did not have the same foresight as Hou to operate a quarry.

In the novel, Hou struggles at first to be a businessman while also holding office. He finally chooses the latter. Putting words in the mouths of Hou and his friends, Zhang tells readers with total frankness that power outweighs wealth in China, since any business owner, no matter how rich, cannot succeed in business without government support.

That is strong proof of the realism of Zhang’s novels. He neither glorifies nor demonizes officialdom. He simply records how village officials have to strike a balance between tending to the villagers and the leaders. For example, given the villagers’ traditional thinking, it was hard to promote cremation. If village officials did not implement any compulsory measures, no villagers would follow the new policy and village officials would be blamed by their leaders. When they enforced cremation, they had to keep a close eye on the mood of the villagers involved and prevent any violent conflicts or even mass incidents, one of the most sensitive areas in Chinese officialdom and which severely impacts an official’s performance appraisal.

Such dilemmas also occurred over family planning. Hou is sent to deal with a woman pregnant – illegally – with her second child. Privately, he sympathizes deeply with the woman and is on the opposite side of the fence to the villagers on this matter, but as a village official, it is his responsibility to implement the government policy. Finally, Hou finds a compromise – he secretly tells the woman to flee the village and reports that he cannot find her.

In Zhang’s novels, most low-ranking officials are ambitious to do something big and influential, whether for the sake of the people or for a sense of achievement or both. Along the way, however, those officials also quite enjoy, or even love the power and benefits their positions bring them and try hard to seize further power through promotion.

Zhang uncovers the guanxi culture in China’s officialdom as part of his story. Good performance, according to Zhang, accounts for only one-third of a promotion, with another third coming from guanxi and the other from one’s tactics. In the novel, Hou is at one point transferred to a marginalized position by the town mayor, just because he had displeased him by getting too close to the town’s Party Secretary who did not get on well with the mayor. Yet, when Hou himself climbed to a higher position, he did the same thing to someone else who knew his secret. According to Zhang, it does not mean that Hou is a bad man, but means that officials including Hou know all too well how to use their power.

In the fictional version of officialdom, the officials spend much of their spare time maintaining their relationship networks. For officials, a major task at Spring Festival, China’s lunar New Year holiday, is to visit higher-level officials and more powerful figures. Many things, both in one’s private life and dealings with the government, become much easier if the officials involved have a good relationship. More importantly, all leaders prefer promoting those who are close to them as their subordinates. Hou Weidong’s promotion, for example, largely depends on his good relationship with the higher-level officials who manage appointments.

“I seldom write about conspiracies and struggles in the novel … I just record the officialdom I was familiar with and the world which I had experienced and witnessed,” Zhang Bing told NewsChina.

When serving as an official, Zhang found that Chinese officialdom has formed a complete mechanism which will not change with a change of leader. In such a mechanism, the bottom-level officials just take charge of the practical, real work. “They are like a screw in a precision machine and the role they can play is limited,” he said.

“The machine has its defects just as humans have genetic defects. Be neither pessimistic nor naïve about those defects,” he added.

‘I’m just a mediocre official’

Yet Zhang did not think he was as capable an official as Hou. Although the economic crisis was the decisive factor in his career change, Zhang said that it was still a deliberate decision. “I used to be a soldier who wished to be a general, but later, I found that I am not capable of being a general,” he said.

Zhang first realized this as the local politics and law department gathered all the promising young officials together. “It is like me practicing running in my childhood. Within a small area, I was the fastest and most skilled, but when I went to participate in the city-level competition, I was not that outstanding,” he said.

Some people who knew Zhang believed he would have been promoted to a city-level official as Hou was in the novel if he had continued to make efforts in officialdom, but Zhang disagreed.

“Yes, I could have gone farther [in officialdom] or reached a higher position, but in the end I still have felt the pain and want to escape,” he said. “One’s destiny is determined by his personality,” he added.

Zhang, now 46, recently added several paragraphs to the novel where Hou’s life seems to go downhill – the old leader whom Hou follows for years dies of cancer while Hou’s mother is also suffering from cancer.

According to Zhang, this comes from his own experiences: people will have less chance of success and see their passion cooling when they become middle aged.

Zhang has still not decided whether or not to end his novel by promoting Hou to provincial official as he originally planned. Zhang himself was moved from the local parks and landscape administration to the local literacy federation, a flat and profitless transfer. Although some speculated that such a transfer was caused by his overtly realistic writing, he denied this.

“The job combines my interests and the [local government’s] need,” he explained, along with benefit of working at the literacy federation: “it is good that I can write in work time as well.”

Zhang’s writing has brought him both fame and fortune. With the royalties he has bought two expensive apartments in areas with good schools. In 2010, Zhang’s name first appeared in the list of China’s richest writers. The Diary of Government Official Hou Weidong has remained one of the best sellers in both online and offline bookstores up to the present.

Interestingly, Zhang entered the officialdom at young age in the face of his father’s strong opposition, but now stands on the same side as his father, firmly against his own daughter becoming a government employee or official. “Thanks to China’s fast development in the market economy, people have multiple career choices other than being an official,” remarks Hou Weidong several times, possibly voicing Zhang Bing’s own feelings.

Old Version

Old Version