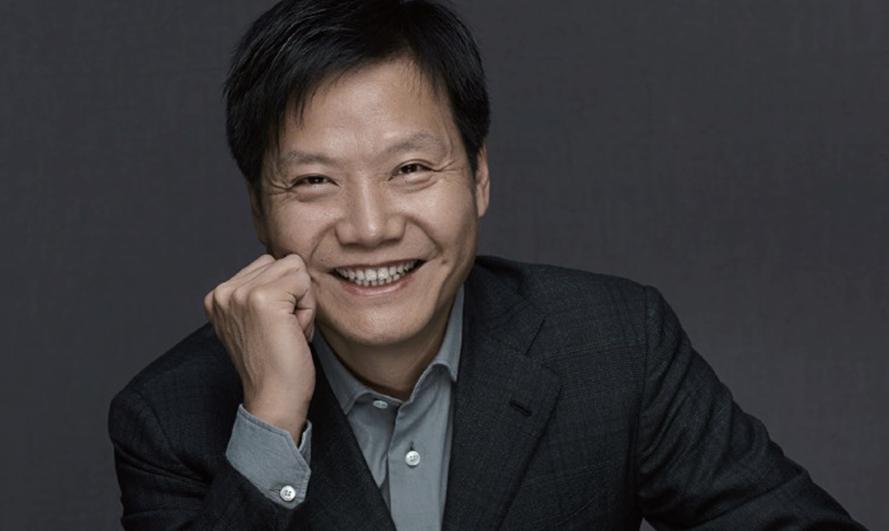

Lei Jun can still vividly recall the moment in May 2011, when his Xiaomi phone, then still under development, was technically ready to make a phone call. The sample phone was fixed to a table, so he had to bend over and press his ear against it.

“It felt like hearing the first cry of your own baby. It sounded so wonderful, as if a brand new world had opened to me,” said the technician-turned-entrepreneur, who masterminded the creation of what was one of China’s best-selling gadgets.

But Lei would have found it challenging to predict the smartphone’s booming popularity in the following couple of years.

After its launch in August of 2011, more than 300,000 Xiaomi phones were sold within a year. In 2012, sales reached 7 million, achieving a stunning growth of 2,300 percent. With an annual growth of at least 160 percent for a few years after that, Xiaomi sold more than 60 million smartphones in 2014, posting 74.3 billion yuan (US$10.68) in revenue and raising its valuation to US$45 billion during its fifth round of financing. At the beginning of 2015, Lei set a sales goal of 80 million – but the company fell short by 10 million sales.

“All work has since been done around that goal,” he said. “Under such pressure, our performance has been getting out of shape. People have been losing their smiles day by day.”

The last two years have been tough for Xiaomi. From first place in the smartphone market, it slipped to fourth, according to data from International Data Corp (IDC). (Xiaomi disputes these figures, saying sales are higher than the IDC numbers.) In the second quarter of 2016, its sales slipped by 38 percent year-on-year. Meanwhile, Fortune magazine reported that the company’s revenue had barely grown in 2015. Headlines that once said “spectacular” were now more likely to say “struggling.”

With growth stalling, the entrepreneur now wants to head back to his original mission. At the age of 40, when he started Xiaomi, Lei was already one of the country’s most important angel investors and a reputed professional manager to whose leadership Kingsoft, one of China’s earliest software companies, owed its successful listing on the main board of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2008.

Lei says he isn’t motivated by just sales. According to him, his dream of building a great company and changing the public’s perception of domestic products, which was initially ignited by the description of Apple founder Steve Jobs’ career in the book Fire in the Valley, still lingers in his mind. It has now boiled down to one concrete task: making the “coolest products.”

On October 25, Xiaomi demonstrated its latest technologies by launching the Note 2 phone and its first high-end smartphone MIX. The Note 2 was highlighted as having a double curved surface. The MIX, jointly designed by Lei and French designer Phillippe Starck, is an assemblage of cutting-edge technologies including a full ceramic body and a full-façade screen.

A short review in Time Magazine highlighted MIX’s 6.4-in screen which makes up 91 percent of the body, comparing it to the two-thirds screen-to-façade ratio on the new iPhone 7. This has been made possible by what the review called a “revolutionary ceramic acoustic technology,” which has “removed the need for an earpiece speaker, and a front camera that is 50 percent smaller than standard.”

Xiaomi’s popularity didn’t traditionally depend on a technological edge, but on marketing techniques. The phones are cheaper than most retail prices, in part because they were mainly sold online, minimizing intermediate costs. This pioneering strategy was widely credited for the smartphone maker’s sweeping market success.

Lei said he aims to break the public’s existing perceptions that equate high quality with high prices. “By increasing the operational efficiency of each segment through the Internet, we have made it possible for high-end products to have an affordable price. This is the innovation of Xiaomi,” Lei said.

Adaptable To Changes

Xiaomi’s quick success was also helped by good timing. Its emergence coincided with China’s first shopping surge for smartphones that mainly took place in the first and second-tier cities, where consumers had already adapted to online shopping.

As the shopping trend now moves to sweep smaller cities and even the countryside, where people are less used to using e-commerce, physical store sales have regained their importance. The last two or three years have witnessed burgeoning sales of local smartphone brands like OPPO and VIVO, which have benefited from their strong dealer networks nationwide. In the cities, the smartphone market is nearly saturated, with replacement phones and upgrades accounting for most new trade instead of new customers.

E-commerce sales only accounted for between 20 and 30 percent of China’s total smartphone retail sales, half of which were Xiaomi phones, Lei said. “Today the core problem we face is how to reach the other 70 to 80 percent of consumers.”

Lei said the exploitation of offline markets will be Xiaomi’s key task this year and the company will rely on physical stores and advertisements to reach the widest number of consumers possible in third and fourth tier cities.

In July, Xiaomi announced for the first time the signing of three popular celebrities to endorse its RedMI phone. Its recently released Note 2 also took the public by surprise, after posters spread on bus stops and subway stations showing Hong Kong movie superstar Tony Leung giving a rare endorsement of the new phone.

The online-to-offline campaign is starting by renovating the company’s existing aftersales service centers, known as the Xiaomi Home, into self-run retail stores along the Apple Store model. Currently, Xiaomi has 43 Homes across the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, with 37 located in shopping malls, where cellphones and accessories are neatly displayed on white shelves and light brown tables.

Since the renovation started in February, the stores have already reported sales performances that have exceeded Lei’s expectations. Most of the stores are expected to achieve annual revenue of between 65 and 70 million yuan (US$9.3 to 10.1 million).

Lei told NewsChina that the operation of these stores will be led by “Internet thinking,” which will continually place efficiency among the top priorities. More growth is expected after efficiency is improved. “In the next three years, our goal is to build 1,000 Xiaomi Homes,” Lei said.

Ecological Chain

In the Xiaomi Homes, cellphones are not the only Xiaomi products to be found. Air and water purifiers, self-balancing scooters, electric rice cookers and many other products that have been developed around the Xiaomi brand in recent years all have their fair share of the 200-square-meter space.

Equipping itself for the oft-predicted era of the “Internet of Things,” Xiaomi initiated the building of its “ecological chain” in 2013. It primarily refers to the development of various Internet accessible devices, such as home appliances and short distance vehicles, which will enable the company to collect consumer data to direct production and which can be controlled by a single Xiaomi phone.

But Xiaomi will not shift its focus away from the making of cellphones, Lei noted. All those products are made by various companies located along Xiaomi’s eco-chain. Xiaomi has invested in these companies, shared with them business models and channel resources, but doesn’t act as a controlling stakeholder.

The eco-chain is a pragmatic strategy Xiaomi deploys to broaden product categories while staying dedicated, Lei told NewsChina. “Xiaomi is now more than one single company. It’s a fleet consisting of dozens of companies, each dedicated to making one product,” he said.

Currently Xiaomi’s eco system has 77 companies. This would have meant 77 departments in a big company. Under traditional management, “That would be exhausting. I have to turn them all into bosses,” Lei said.

Within no more than three years, Lei claimed, many of these products, such as wristbands and air purifiers, have already become the best-sellers in their categories. By November, 16 of them had posted over 100 million yuan in annual revenue, of which 3 have grossed an annual revenue of more than one billion yuan.

Meanwhile, Mijia, an app through which a Xiaomi phone can link to and control all of the brand’s intelligent products, reports registration of nearly 50 million devices in total, with 5 million concurrently connected at its peak, according to Lei.

“From the basic big data to the platform, and then the all-encompassing intelligent devices, Xiaomi has started to create a total eco system,” said Wang Junxiu, head of the information society research division under China Information Economics Society.

Other experts are skeptical, however. Clay Shirky, who wrote Little Rice: Smartphones, Xiaomi, and the Chinese Dream, told Bloomberg that “It’s not clear that there’s a business-to-consumer model that works for the so-called Internet of Things. What do you want your fitness band to say to your rice cooker? Why does your television need to be in communication with your Segway? No one has gotten that right, not even Amazon.”

Lei plans for the products in Xiaomi’s eco system to cover 100 categories in the future. By then, he claims, Xiaomi’s retail platform will attract a much larger customer flow than a single product could. Without an adequate customer flow, Lei said, Xiaomi would be just like any traditional manufacturer, who had to sell their product worth 1,000 yuan at 3,000 or even 5,000.

“That is not China’s future. China’s future is an efficiency revolution,” he said. “The eco chain is of great value to us in building a highly efficient world-class retail group and exploring new users.”

Old Version

Old Version